ESG / CSR

Industries

What is natural capital?

When we think about capital, our minds tend to go straight to money, infrastructure, or perhaps the skills of a workforce. But there’s another form of capital that underpins every economy, and it doesn’t show up on a company balance sheet.

Natural capital refers to the world’s stock of natural resources – including air, water, soil, biodiversity, and ecosystems – that provide essential goods and services to humanity.

It’s nature’s contribution to the economy. Forests that clean the air and store carbon. Oceans that regulate the climate and provide food. Wetlands that purify water and protect against flooding. These aren’t just scenic landscapes, they’re valuable, functioning assets that support livelihoods, health, and economic growth.

Yet despite their critical role, these natural systems are often ignored in economic decision-making until they start to fail.

As pressure on the planet intensifies, governments, businesses, and financial institutions are beginning to rethink how nature is valued. Natural capital is a useful concept that helps embed environmental limits into our economic models, investment strategies, and long-term planning.

In this article, we’ll explore what natural capital is, why it matters, and how it can be used to reshape the way we measure success.

What is natural capital?

In other words, just as financial capital generates income, natural capital generates essential services that sustain life, from food and clean water to climate regulation and pollination.

It’s a concept grounded in environmental economics, aimed at helping policymakers and businesses understand the true value of nature’s contributions. By framing nature as a form of capital, it becomes easier to incorporate environmental risks and benefits into decision-making processes.

Types of natural capital

Natural capital can be broken down into three broad categories:

| Type of natural capital | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Renewable resources | Can regenerate over time if managed sustainably | Forests, fisheries, freshwater |

| Non-renewable resources | Finite and cannot be replenished on a human timescale | Fossil fuels, minerals |

| Ecosystems | Living systems that provide ongoing services and support biodiversity | Wetlands, coral reefs, grasslands |

These natural assets interact with each other, regenerate under the right conditions, and provide direct and indirect support for every aspect of modern life.

This is where natural capital differs from traditional environmental thinking. Rather than viewing nature solely in terms of conservation, it positions the environment as an economic asset – one that requires investment, maintenance, and, when necessary, restoration.

Natural capital vs other types of capital

To fully grasp the importance of natural capital, it helps to see how it compares with other forms of capital we already measure and manage. The table below illustrates this:

| Capital type | What it includes | How it contributes to value |

|---|---|---|

| Natural capital | Ecosystems, resources, biodiversity | Provides raw materials, regulates climate, supports life |

| Human capital | Skills, knowledge, health | Powers innovation, labour, education |

| Social capital | Institutions, relationships, trust | Enables cooperation, governance, and social cohesion |

| Financial capital | Money, investments, infrastructure | Facilitates trade, investment, economic growth |

Why is natural capital important?

1. Nature supports the economy

It’s easy to forget that supply chains begin with nature. Agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and even some forms of energy all rely directly on natural systems to function. According to the World Economic Forum, over half of global GDP – around $44 trillion – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services.

When ecosystems degrade, entire industries are put at risk, from farming and tourism to insurance and finance.

Companies are increasingly aware of this. A growing number now include environmental dependencies and risks in their financial reporting, particularly as investors and regulators demand more transparent disclosures.

2. Nature regulates critical systems

Beyond the direct economic benefits, natural capital provides crucial regulating services. Forests and wetlands, for example, absorb and store carbon, helping to mitigate climate change. Soils cycle nutrients, and oceans act as heat sinks that stabilise global temperatures.

Without these systems functioning properly, we lose not just biodiversity, but the life-support services that make the planet habitable.

This is where the true value of natural capital lies – in the stability it provides across environmental, economic, and social domains.

3. Nature builds resilience

Healthy ecosystems act as buffers against shocks. Mangroves and coral reefs help protect coastal communities from storm surges. Urban green spaces reduce heat during extreme weather events. Diverse ecosystems are also more resilient to pests, disease, and climate variability.

Investing in natural capital is often more cost-effective than building artificial alternatives and can bring other benefits for health, biodiversity, and local communities.

4. Nature contributes to well-being

There’s a growing body of research linking nature to mental and physical health. Access to green spaces improves cognitive function, reduces stress, and promotes physical activity. Cultural and spiritual connections to landscapes also form a vital part of many communities' identities.

Examples of natural capital and why they matter

Before we dive into how natural capital is measured, it’s worth pausing to look at what it actually includes, and why these assets are so valuable.

The table below outlines examples of different types of natural capital and the essential services they provide.

| Natural capital asset | Why it matters | Key services provided |

|---|---|---|

| Forests | Store carbon, regulate rainfall, support biodiversity, and provide timber | Climate regulation, water filtration, provisioning services |

| Wetlands | Act as natural water filters and buffers against flooding | Water purification, flood control, habitat provision |

| Oceans and coral reefs | Support fisheries, regulate climate, and protect coastlines | Food provisioning, carbon absorption, storm protection |

| Soils | Enable food production and store carbon | Nutrient cycling, food provisioning, carbon sequestration |

| Pollinators (e.g. bees) | Crucial for food production and plant reproduction | Crop pollination, biodiversity maintenance |

| Urban green spaces | Improve air quality, reduce heat, and support mental health | Cooling, air purification, cultural services |

| Mountains and glaciers | Store freshwater and support tourism and cultural identity | Water provisioning, cultural and recreational value |

Natural capital accounting

While the value of nature is increasingly recognised, it’s still rarely measured - at least not in the same way we account for financial or physical assets.

Natural capital accounting is an approach that aims to measure, quantify, and sometimes assign monetary value to natural assets and the benefits they provide. In short, it helps make the invisible visible.

The goal isn’t just to put a price on nature. It’s to help decision-makers understand the real cost of environmental degradation and the long-term value of investing in nature.

How it works

There are several ways to carry out natural capital accounting. Some approaches focus on physical quantities (such as hectares of forest lost), while others attempt to quantify the economic value of the services ecosystems provide (such as water filtration or carbon storage).

This data can then be used to:

- Inform policy and land-use decisions

- Identify environmental risks in business operations

- Support long-term investment strategies

- Report on environmental performance and sustainability

Governments, companies, and financial institutions are increasingly using natural capital accounts to support sustainability planning and ESG reporting. A number of frameworks and initiatives have emerged to guide this process, including:

| Framework or initiative | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Natural Capital Protocol | A decision-making framework for businesses to identify, measure and value their interactions with natural capital |

| SEEA (System of Environmental-Economic Accounting) | A UN-backed framework that integrates environmental data with national economic accounts |

| Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) | A global initiative encouraging businesses to assess and disclose nature-related risks and opportunities |

Natural capital accounting isn’t perfect, and it’s not a silver bullet. Many services provided by nature are difficult to quantify. But it’s a step toward integrating the environment into systems that have long excluded it.

Threats to natural capital

Despite its importance, natural capital is being eroded at an alarming rate. From deforestation and pollution to climate change and habitat loss, many of the planet’s natural systems are under increasing pressure, often as a direct result of economic activity.

When natural capital is degraded or lost, the services it provides don’t just disappear, they stop supporting communities, economies, and ecosystems.

Some of the biggest threats include:

Over-exploitation of resources

Extracting natural resources faster than they can regenerate leads to long-term decline. This includes unsustainable logging, overfishing, and soil depletion due to intensive agriculture. When ecosystems are pushed beyond their limits, they lose their ability to function, sometimes permanently.

Pollution

Pollutants from industry, agriculture, and transport systems contaminate air, water, and soil, weakening the resilience of natural capital. Excess fertiliser use, for example, can lead to dead zones in rivers and oceans, stripping ecosystems of oxygen and biodiversity.

Climate change

Rising temperatures, shifting weather patterns, and extreme events are already altering ecosystems around the world. Climate change not only damages natural capital, it also reduces its ability to act as a buffer against environmental shocks.

Land-use change and habitat destruction

Urban expansion, mining, infrastructure development, and agricultural conversion are fragmenting and destroying habitats at scale. Once diverse, interconnected ecosystems are reduced to isolated patches, often too small or degraded to support their original biodiversity.

Invasive species

Global trade and travel have increased the spread of non-native species, which can outcompete local plants and animals. This can destabilise ecosystems and reduce the services they provide, such as pollination or pest control.

Protecting and restoring natural capital

Recognising the value of natural capital is only the first step, the real challenge is protecting what remains and restoring what’s been lost. This requires action at every level, from national governments and global institutions to businesses and communities.

Sustainable resource management

Many of the services nature provides can be restored, but only if they’re used within ecological limits. That means setting catch limits for fisheries, managing forests for both conservation and production, and reducing water use in areas facing scarcity.

By keeping use within regenerative boundaries, we can maintain natural capital.

Ecosystem restoration

Where natural systems have already been damaged, targeted restoration can help bring them back. Reforestation, wetland regeneration, soil rehabilitation, and rewilding are all strategies that aim to rebuild the structure and function of ecosystems.

According to the UN, restoring just 30% of degraded land could prevent up to 70% of expected species extinctions and sequester hundreds of millions of tonnes of CO2 every year.

Policy and regulation

Governments play an important role in protecting natural resources. This includes everything from legal frameworks that safeguard biodiversity and land rights to subsidies and tax reforms that reward conservation rather than environmental harm.

Some countries have gone further, integrating natural capital into national accounts, requiring environmental impact assessments, or protecting large areas through permanent conservation status.

Private sector investment

Businesses and financial institutions are starting to integrate natural capital into their risk frameworks, sustainability strategies, and product design. Investing in nature is no longer seen as a cost, but as a way to reduce risk, build resilience, and create new opportunities.

Nature-based solutions, such as regenerative agriculture, green infrastructure, and biodiversity credits, are emerging as practical tools for aligning profit with planetary boundaries.

Community and Indigenous leadership

Local and Indigenous communities manage a significant share of the world’s remaining natural capital, often more effectively than state or private actors. Their knowledge systems, land stewardship practices, and long-term relationships with nature are crucial for conservation success.

Supporting community-led initiatives is one of the most effective and equitable ways to protect natural capital.

The future of natural capital

Natural capital is becoming central to the way governments, investors, and businesses think about risk, value, and long-term resilience. As environmental pressures grow, natural capital will play a bigger role in shaping policy, investment, and corporate strategy.

Integrating nature into financial systems

There’s growing momentum to account for natural capital in national budgets, corporate balance sheets, and financial disclosures. Initiatives like the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) are pushing companies to assess and report their dependencies and impacts on nature, much like they already do for climate.

Investors are increasingly asking for nature-related data, and companies that fail to account for it could face reputational, regulatory, and financial risks.

Linking climate, biodiversity, and development

Climate and biodiversity are often treated as separate issues, but in reality, they’re deeply interconnected. Forests, oceans, peatlands, and grasslands are critical carbon sinks, meaning that protecting natural capital is also essential for meeting climate targets.

At the same time, development goals depend on healthy ecosystems, from food security and disaster resilience to clean water and livelihoods. Future planning will need to bring these agendas together.

Nature markets and biodiversity credits

As carbon markets mature, there’s increasing interest in creating credible, scalable nature markets. These include biodiversity credits, habitat banking, and other mechanisms that reward conservation and restoration.

Done right, these tools could channel finance into ecosystem protection and give landowners incentives to maintain natural capital. But they also raise questions about governance, equity, and what counts as legitimate environmental value.

Innovation and data

Advances in remote sensing, AI, and environmental modelling are making it easier to monitor the health of ecosystems and track changes in natural capital over time. Better data will make it easier to manage natural capital and to hold actors accountable when it's being degraded.

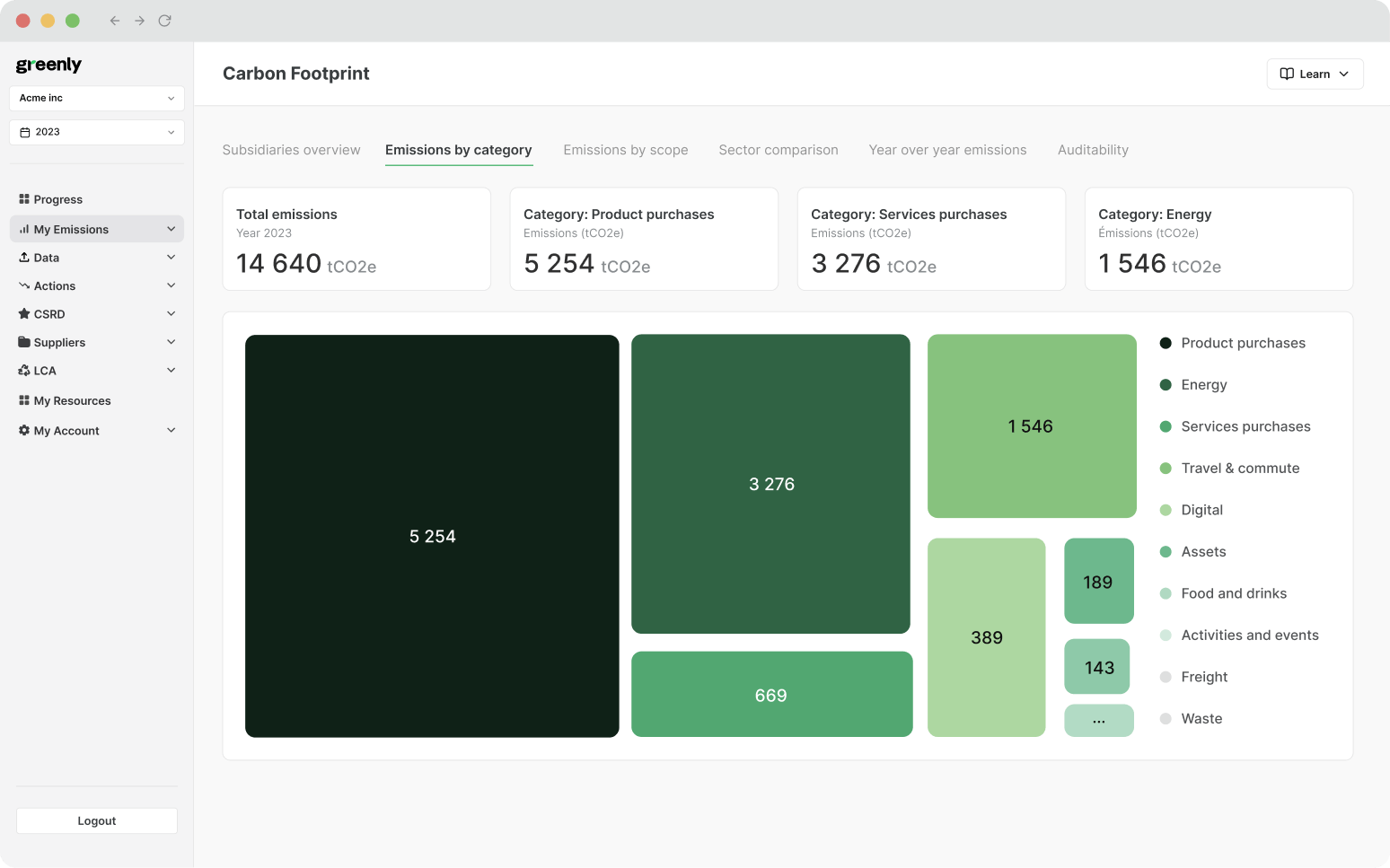

How Greenly can help your company

Understanding the value of natural capital is one thing, but turning that understanding into action requires data, tools, and clear strategies. That’s where Greenly comes in.

We help companies measure, track, and reduce their environmental impact, providing the insights needed to make more sustainable, resilient decisions.

Here’s how Greenly can support your sustainability journey:

- Carbon footprint analysis: Our platform calculates your full Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, helping you understand where your greatest environmental impacts lie – from operations to supply chains.

- Tailored emissions reduction plans: Based on your data, we develop practical, science-aligned strategies to reduce your carbon footprint and identify where you can take immediate action.

- Supplier engagement and supply chain transparency: Greenly helps you assess supplier performance, identify hotspots, and choose more sustainable partners, supporting a more resilient, lower-risk supply chain.

- Support for science-based targets: We guide companies through the process of setting and reaching science-based targets, aligned with global climate goals and regulatory frameworks.

- Regulatory and ESG reporting support: Whether you need to comply with new climate disclosure regulations or improve your ESG reporting, our tools make it easier to communicate progress and stay ahead of requirements.

Greenly gives you the data and direction you need to reduce your carbon footprint and become more sustainable. Get in touch today to find out more.