ESG / CSR

Industries

Green Belts Explained

As cities expand and housing demand intensifies, one question keeps resurfacing: how do we build more homes without losing the green spaces that make urban life liveable?

For decades, planners have tried to strike a balance between development and preservation by setting aside land around towns and cities where building is strictly controlled. These areas, often referred to as green belts, are intended to stop cities from sprawling endlessly into the countryside, while safeguarding natural landscapes, farmland, and biodiversity.

The idea began in the early 20th century and has since taken hold in countries across the world. In the UK, green belt policy is one of the most enduring features of the planning system. In Canada, Germany, Brazil, and beyond, similar approaches have emerged in response to rapid urbanization and environmental concerns.

- What green belts are and why they exist

- How different countries implement green belt policies

- The key benefits of green belts – from climate resilience to urban regeneration

- The criticisms and challenges they face today

- How green belt strategies could evolve in the future

What is a green belt?

Green belts aren’t parks or reserves in the traditional sense. They often include farmland, woodland, grassland, or even scrubland - the key factor is that they are kept open and largely undeveloped.

Public access to this land varies; in some cases, green belt land is used for walking or leisure activities, while in others it remains private and agricultural.

While the core aim is to stop cities from growing outwards in an uncontrolled way, green belts are also seen as a way to:

- Preserve the separation between neighbouring towns and villages

- Maintain biodiversity and natural habitats near urban centres

- Encourage brownfield regeneration by funnelling development back into underused urban areas

- Offer a buffer against air pollution and climate impacts like urban heat

But not all green belts are the same. In some places, they’re continuous rings that fully encircle a city. In others, they’re made up of fragmented pockets of land, shaped by land ownership and local planning decisions. And while the principle is shared across many countries, how green belts are defined and enforced can vary widely depending on the context.

Green belts around the world

While green belts are often associated with the UK, the idea of protecting land around cities to control growth isn’t unique to one country. Versions of this policy have been adopted in various forms around the world, shaped by different planning philosophies, political contexts, and environmental concerns.

In the United Kingdom, green belts are a long-standing and central part of the national planning system. First introduced in the 1930s and expanded after World War II, they now cover around 12.6% of England’s land. Although designated and managed by local government, green belts in England operate under a national framework. The government’s National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) sets out five green belt purposes:

- To check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas

- To prevent neighboring towns from merging into one another

- To assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment

- To preserve the setting and special character of historic towns

- To assist in urban regeneration by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land

In practice, this means that development on green belt land is only allowed in very special circumstances. Most new building is considered inappropriate development and is subject to strict planning controls or the rejection of planning applications. The policy has played a significant role in shaping how cities like London and Manchester have grown, curbing their spread while encouraging more efficient development within existing urban areas.

Supporters argue that green belts have helped preserve the countryside, maintain the identity of towns and villages, and protect biodiversity close to urban centres. Critics, on the other hand, say they’ve contributed to housing shortages, pushed development further out, and led to longer commutes. London’s green belt, in particular, has been central to debates around housing access, urban containment, and future reform. Even so, the principle of the green belt remains one of the most politically enduring features of UK planning.

Canada does not have a single, country-wide green belt policy. Instead, it has a range of regionally managed green belts and land protection initiatives designed to curb urban sprawl and protect farmland and ecosystems.

The Ontario Greenbelt, a vast, 2-million-acre protected zone around the Greater Toronto Area that was created in 2005, is the most prominent. But other examples exist too: the Ottawa Greenbelt, established in the 1950s; British Columbia’s Agricultural Land Reserve, which restricts non-agricultural development across the province; and Quebec’s agricultural zones, which function similarly.

These policies reflect Canada's emphasis on both environmental conservation and the safeguarding of agricultural land near expanding cities.

Germany employs a wide variety of green belt strategies, combining historical conservation efforts with proactive urban planning.

The largest example is the German Green Belt (Grünes Band), a 1,393 km ecological corridor tracing the former East-West border. Once a heavily fortified "death strip", this area has transformed into a haven for biodiversity, hosting over 1,200 rare species and 146 distinct habitat types. It spans nine federal states, including Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt, and Lower Saxony, and is considered the backbone of Germany's ecological network.

Beyond the Grünes Band, Germany has implemented regional green belts as part of its spatial planning policies. The Frankfurt Green Belt, for example, encompasses approximately 8,000 hectares, covering a third of the city's area, and includes forests, parks, and agricultural land. Similarly, the Ruhr region has established green belts to manage urban growth and preserve open spaces amidst its dense industrial landscape.

These initiatives reflect Germany's commitment to integrating nature conservation with urban development, ensuring that green spaces are preserved for ecological balance, recreation, and cultural heritage.

Both Brazil and Australia have taken broader landscape-scale approaches to limiting urban expansion. In Brazil, the São Paulo Green Belt Biosphere Reserve, established under UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere Programme, encircles the city with a mosaic of parks, forests, and rural land aimed at conserving the Atlantic Forest and providing essential ecosystem services to urban residents.

In Australia, cities like Melbourne have introduced “green wedges”: non-urban zones set aside for agriculture, conservation, and recreation that help shape the city’s outward growth. These approaches are less about enforcing hard boundaries and more about integrated regional planning.

In the United States, there’s no national green belt policy, and the term itself isn’t widely used in planning. However, some cities have introduced similar mechanisms. The most notable example is Portland, Oregon, which implemented an urban growth boundary (UGB) in the 1970s to restrict suburban sprawl and preserve surrounding farmland.

Elsewhere, open space preservation is usually handled through a mix of zoning rules, conservation easements, and land trusts. Because land-use policy is largely set at the state and municipal level, the effectiveness and intent of these efforts vary widely across the country.

The benefits of green belts

While green belts were initially designed to curb urban sprawl, their importance now extends well beyond that original purpose. When well-planned and properly maintained, green belts offer a range of environmental, social, and even economic advantages.

Here's how they can support both people and planet:

🌿 Environmental protection

Green belts protect ecosystems and wildlife habitats by preventing development across large areas. They help maintain biodiversity, regulate temperatures, reduce flood risk, and improve air and water quality.

🚶♀️ Wellbeing and open space

Accessible green belts support walking, cycling, and recreation. Proximity to green space is linked to better mental and physical health, reduced stress, and improved overall wellbeing in urban settings.

🏙️ Urban regeneration

By curbing outward growth, green belts help focus development within existing cities. This encourages the reuse of brownfield land and supports compact, walkable neighbourhoods over sprawling suburbs.

🌾 Agriculture and food

Many green belts include working farmland. Protecting this land preserves local food systems, reduces transport emissions, and maintains agricultural capacity near cities.

🌍 Climate and economy

Though they limit development, green belts offer long-term value through climate mitigation, public health, and tourism. They also support local economies and provide ecological services across regions.

Criticisms of green belts

Here are some of the main challenges and criticisms:

🏘️ Housing shortages

Green belts can limit land supply near high-demand cities, contributing to rising housing costs and pushing development further out. Critics argue that low-quality green belt land could be repurposed for affordable housing in a sustainable way.

🚗 Leapfrogging and sprawl

While intended to prevent sprawl, green belts can push new development beyond their boundaries, leading to disconnected suburbs, longer commutes, and greater car dependency – all of which raise emissions.

⚖️ Land inequality

Green belts can reinforce spatial inequality by protecting wealthy areas from change while limiting housing options for others. This may lock younger or lower-income people out of well-located neighbourhoods.

🌱 Limited ecological value

Not all green belt land is ecologically rich or visually appealing. Some is intensively farmed or inaccessible. Critics argue that these areas should be assessed more carefully for restoration or redesignation.

🧱 Policy rigidity

Strong political support for green belts can make reform difficult. Local authorities often face pressure to maintain protections, even when flexibility could help address housing or infrastructure challenges.

🔄 Calls for reform

Some planners advocate for a more nuanced, criteria-based approach to green belts – one that protects what matters most while allowing for strategic, sustainable change where it’s needed.

The future of green belts

Green belts were once seen as a simple solution to urban sprawl - a fixed line drawn to preserve open space and define where cities should end. But today’s challenges are more complex. Climate resilience, housing demand, food security, and biodiversity loss are reshaping how we think about land use and raising new questions about the role of green belts in a fast-changing world.

Rather than being scrapped or left untouched, many experts now argue that green belts need to evolve.

A growing number of policymakers and urban planners are calling for a shift in mindset, away from treating green belts as static, untouchable buffers, and toward managing them as active, multi-purpose spaces.

That might mean supporting regenerative agriculture, restoring degraded land to native habitat, or improving public access to support health and wellbeing. In some cases, it could involve limited, well-planned development on low-value land and brownfield sites, but only where this aligns with broader sustainability goals.

Green belts could also play a greater role in helping cities adapt to climate change. Tree planting and soil restoration within green belt land could help store carbon, manage water, and reduce the impacts of extreme heat.

And by connecting fragmented habitats, they can form part of wider ecological networks that support biodiversity near urban centres. In this sense, green belts don’t just prevent harm, they could actively deliver environmental and social value.

As debates continue, one underlying question remains: who benefits from the current system, and who is left out? Reforming green belt policy should also be about rebalancing priorities, improving transparency, and making sure green space serves the wider public, not just a privileged few.

That means integrating green belt decisions with affordable housing strategies, sustainable transport planning, and long-term resilience goals, not treating them as a standalone issue.

What about Greenly?

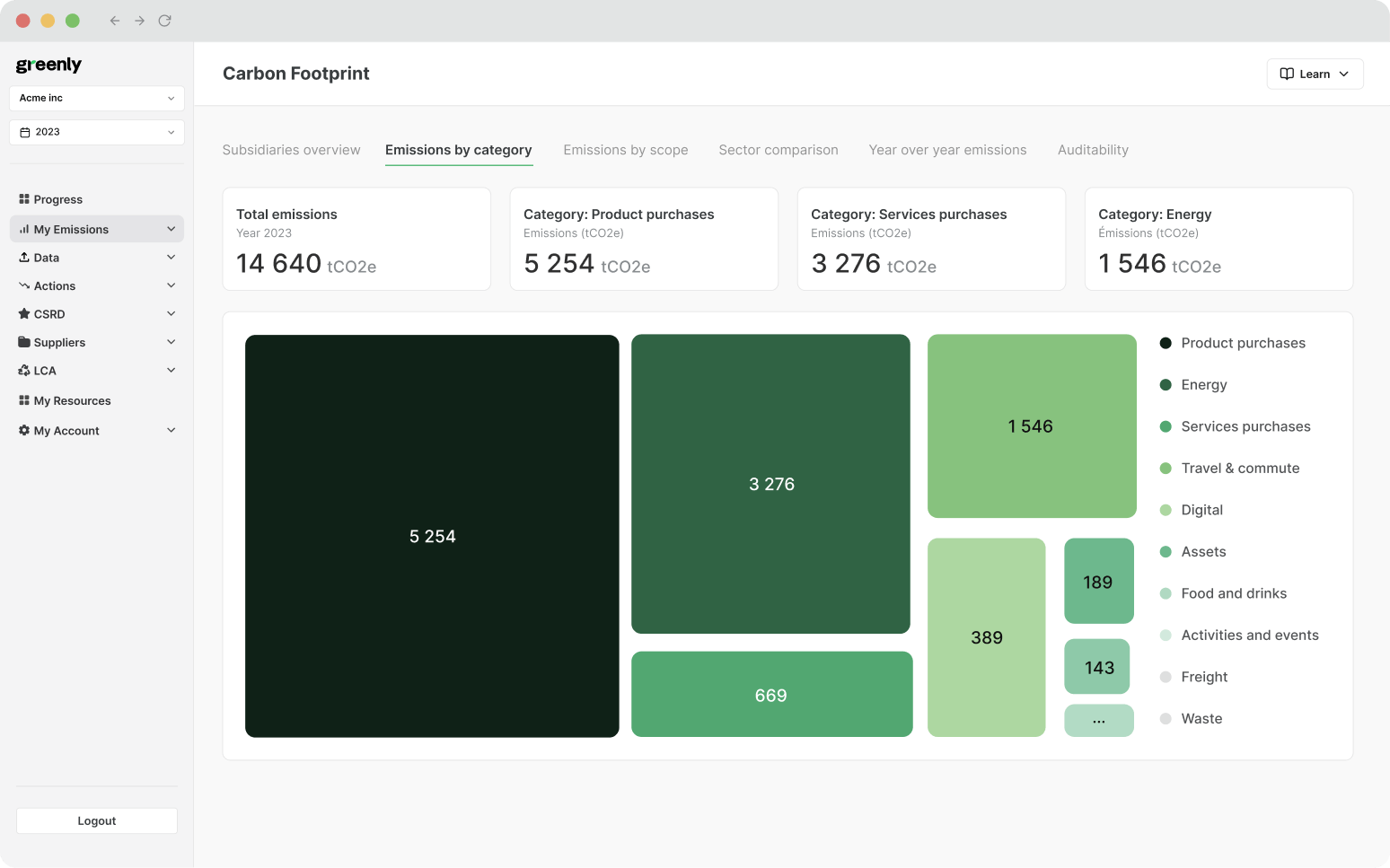

Greenly helps companies take control of their carbon footprint with accessible, data-driven tools and expert guidance. Our platform is designed to make emissions tracking and reduction simple, actionable, and aligned with the latest standards.

Here’s what we offer:

| What Greenly Offers | How It Helps |

|---|---|

|

Comprehensive emissions tracking

|

Monitor Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions across your operations with detailed, real-time insights. Gain visibility into your full carbon footprint and identify key areas for reduction. |

|

Tailored decarbonization strategies

|

Identify where emissions are highest and take targeted action with sector-specific recommendations. Greenly helps turn your data into an actionable reduction roadmap. |

|

Supplier engagement tools

|

Collaborate with suppliers to improve emissions data quality and reduce upstream impacts. Engage your value chain and build more sustainable procurement practices. |

|

Science-based target alignment

|

Set and work toward ambitious climate goals in line with SBTi criteria. Greenly provides expert support to align your strategy with global standards and stay ahead of regulations. |

Whether you're just getting started or advancing an established climate strategy, Greenly gives you the insights and support needed to accelerate your transition to net zero. Get in touch with us today to find out more.