ESG / CSR

Industries

Rearming Europe: Counting the Carbon “Bootprint”

Rearming Europe: Counting the Carbon “Bootprint”

In 2025, Europe is rearming on a scale unseen since the Cold War.

Following a dramatic shift in U.S. foreign policy under President Donald Trump – including the suspension of military aid to Ukraine and calls for NATO allies to spend up to 5% of their GDP on defense – European leaders have launched a sweeping new era of military buildup.

Plans like the European Union’s €800 billion "ReArm Europe" package, Germany’s historic abandonment of its constitutional “debt brake” to fund defense, and France’s push to raise military spending to 3.5% of GDP, signal a collective urgency to strengthen Europe's security in an uncertain world.

Yet there is a dimension of this rearmament drive that remains largely hidden from public debate: its environmental cost.

In this investigation, we look beyond the budgets and battalions to ask:

What will Europe’s rearmament mean for greenhouse gas emissions?

Using original calculations and the latest defense spending data, we estimate the potential carbon impact of Europe's military surge and highlight why greater transparency on military emissions is urgently needed if Europe is serious about its climate commitments.

Militaries: The hidden emissions

When we talk about climate change, militaries rarely make the headlines. Yet armed forces are among the world's largest consumers of fossil fuels, and some of the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

To put this into context:

- That’s more than the total emissions (3.7%) of the entire continent of Africa (home to 1.4 billion people).

- It’s also higher than the combined emissions of the global aviation (2.5%) and shipping (2%) sectors, which together account for around 5%.

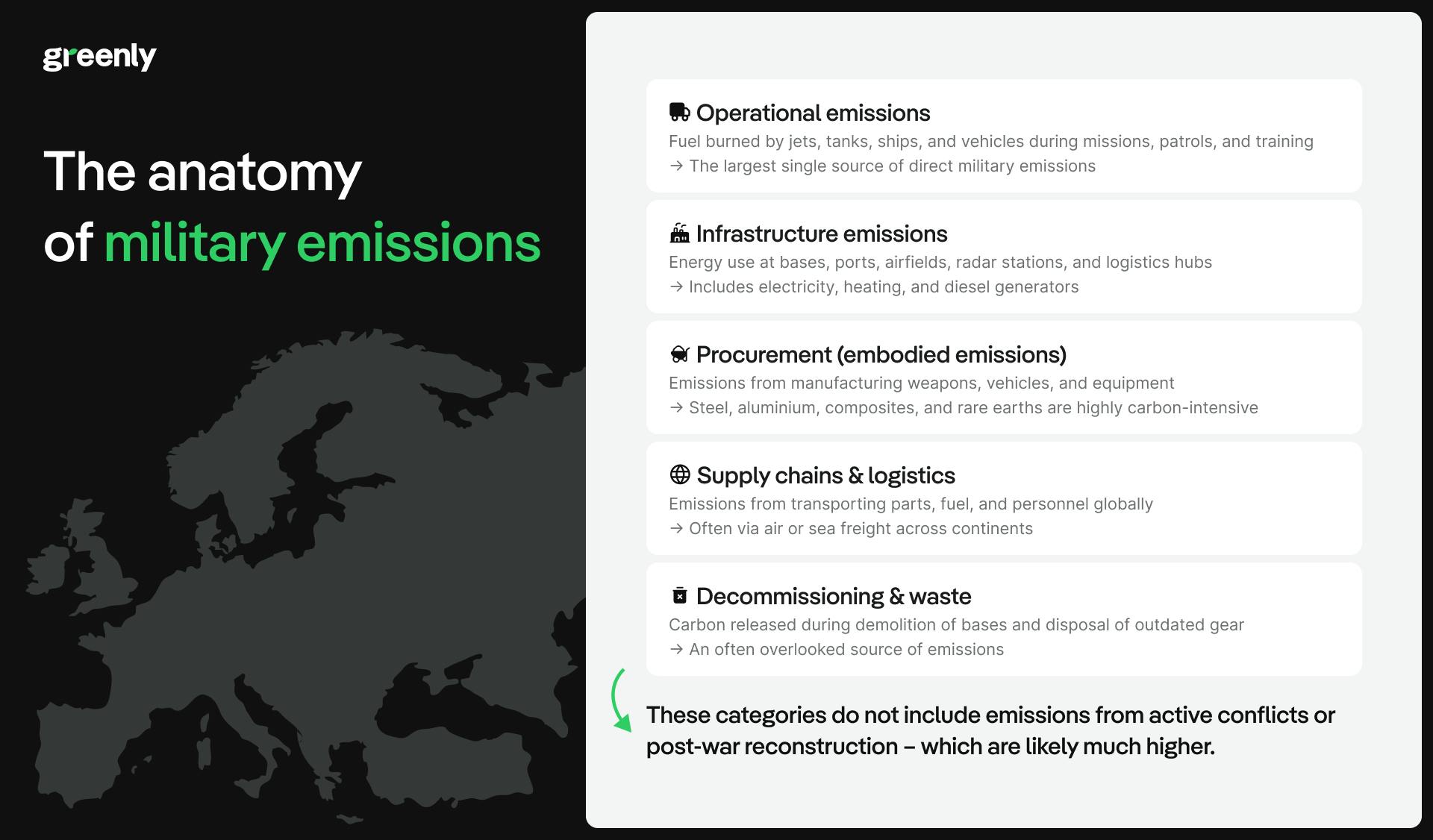

What’s included in military emissions?

When experts estimate the climate impact of militaries, they typically include:

Operational emissions

Fuel burned by fighter jets, tanks, ships, helicopters, and military vehicles during peacetime and wartime operations. (Scope 1)

Infrastructure emissions

Energy use in maintaining military bases, barracks, ports, airfields, radar stations, and supply depots worldwide. (Scope 2)

Procurement emissions

The carbon footprint of manufacturing weapons, munitions, and military equipment (e.g. tanks, aircraft, satellites). (Scope 3.1)

Logistics & supply chains

Emissions tied to transporting materials, spare parts, and troops around the globe. (Scope 3)

Waste & decommissioning

Emissions from dismantling outdated weaponry, equipment, and military bases. (Scope 3)

Yet these estimates still do not capture:

- The emissions from active conflicts (e.g. the destruction of cities and destroyed infrastructure).

- Post-conflict reconstruction emissions can be enormous as countries rebuild after war.

This means that the 5.5% figure is likely a conservative estimate.

Example: The US military

The U.S. Department of Defense is a striking example of military carbon intensity:

Why the military footprint matters

The scale of military emissions matters because:

- Climate models assume dramatic emissions cuts across all sectors – including transportation, energy, and industry – to meet 1.5°C targets under the Paris Agreement.

- If military emissions are left unchecked, they could significantly undermine these targets.

- Rising global military budgets (up 9.4% in 2024) mean that, unless addressed, the carbon footprint of militaries will continue expanding just as civilian sectors are asked to shrink theirs.

Yet until now, militaries have been allowed to operate outside most international climate rules – a major gap that environmental researchers and NGOs are increasingly calling attention to.

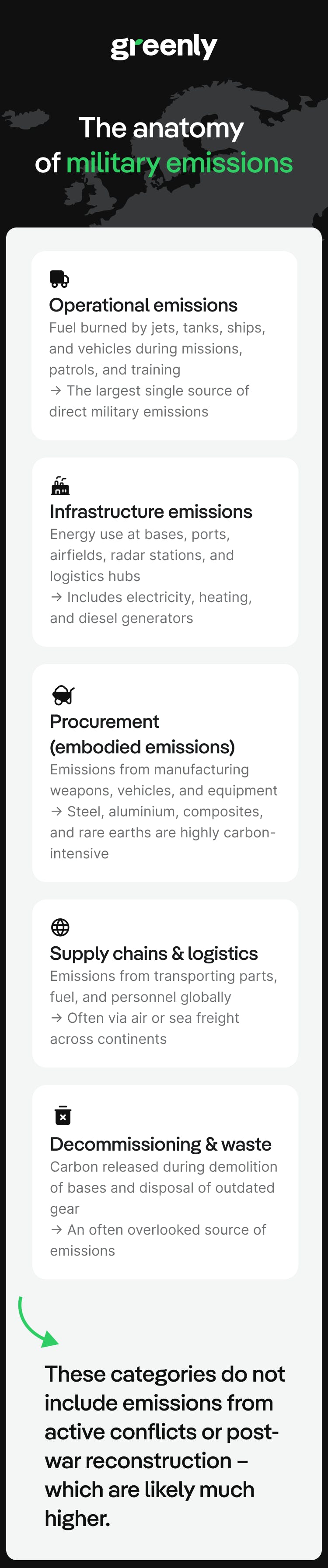

Why military emissions are largely invisible

This is due to longstanding gaps in international climate agreements, and it has major consequences for efforts to meet global climate goals.

Climate agreements carved out exemptions for militaries

Since the 1990s, international climate treaties have allowed special treatment for military activities:

The Kyoto Protocol (1997) permitted countries to exclude emissions from military operations abroad.

The Paris Agreement (2015) left military emissions entirely voluntary. No country is legally obliged to report them, let alone reduce them.

This was justified on national security grounds: governments argued that disclosing detailed military energy use or logistics data could compromise operational secrecy.

The result: patchy and inconsistent reporting

Because of these loopholes:

- Some countries report only partial data (e.g. emissions from domestic military bases, but not deployed forces or arms production).

- Others bundle military emissions under broad public-sector categories, making them difficult to separate.

- Many countries do not report military emissions at all.

There is no mandatory international framework for military emissions accounting.

Consequences for climate action

This lack of transparency means:

How military activities generate emissions

Military carbon emissions can be broadly divided into two categories: Operational emissions (running armed forces day-to-day) and embodied emissions (linked to manufacturing military equipment and infrastructure).

Operational emissions: Fuel and energy use

Armed forces are among the world’s heaviest consumers of fossil fuels. Their daily operations generate massive emissions, mainly through:

Aircraft operations

Fighter jets, cargo planes, and helicopters burn vast amounts of fuel. The F-35, for example, emits around 15 tonnes of CO₂ per hour.

Land vehicles & tanks

Military tanks like the Leopard 2 use up to 500L of diesel per 100 km off-road – many times more than a civilian truck.

Naval vessels

Warships burn heavy marine fuel. One US destroyer emits ~250 tonnes of CO₂ daily – European frigates have similar footprints.

Military bases

Bases require energy 24/7 – heating, lighting, radar, logistics – often powered by fossil-heavy grids or diesel generators.

Training & readiness

NATO's expanded patrols and air policing post-Ukraine have made training and exercises increasingly emissions-intensive.

Embodied emissions: Weapons production and supply chains

While military emissions are often associated with fuel consumption during operations, a significant and frequently overlooked contributor is the embodied emission - ie. the greenhouse gases released during the production and supply chain processes of military equipment and infrastructure.

The carbon footprint of military hardware

Modern military platforms are constructed using materials that are highly carbon-intensive to produce. For example, the F-16 Fighting Falcon, the most widely used fighter jet globally, has an airframe composed of approximately:

| Material | Share of composition |

|---|---|

Aluminium |

78.4% |

Steel |

11% |

Glass fibres |

6.8% |

Composites |

3% |

Titanium |

0.8% |

Each of these materials carries a substantial carbon footprint per kilogram produced:

| Material | Carbon footprint (kg CO₂e per kg) |

|---|---|

Aluminium |

Global average: 16.1 kg CO₂e/kg EU average: 6.8 kg CO₂e/kg Up to 20+ kg CO₂e/kg depending on energy source |

Steel |

Average: 1.5 kg CO₂e/kg Range: ~0.68 kg to 2.33 kg CO₂e/kg depending on production method |

Titanium |

17 kg CO₂e/kg |

Carbon fibre composites |

24 kg CO₂e/kg |

Given that military aircraft, tanks, and helicopters can weigh between 10 to 70 tonnes, the embodied emissions from material production alone are significant. This doesn't account for additional emissions from manufacturing processes, transportation, and assembly.

Global supply chains

The production of military equipment often involves complex, global supply chains. For example, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program includes nine partner countries (including the U.S.) and over 1,650 suppliers worldwide. Components are manufactured across continents and then shipped to assembly locations, primarily in the United States and Italy. This extensive logistics network contributes additional emissions through air and sea freight.

Critical minerals

Advanced military technologies rely heavily on rare earth elements (REEs) such as neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium, which are essential for components like permanent magnets in precision-guided munitions and radar systems. The extraction and processing of these minerals are energy-intensive, with emissions ranging from 165 to 672 kg CO₂e per tonne of REE metal produced.

Moreover, the demand for REEs is projected to increase significantly over the next few decades, driven by both military and renewable energy sectors.

Infrastructure

Beyond equipment, the construction of military infrastructure, such as bases, airfields, and shipyards, adds to the carbon footprint. Materials like cement and steel are primary contributors:

- Cement production accounts for approximately 8% of global CO₂ emissions.

- Steel production is responsible for about 7% of global CO₂ emissions.

Military construction projects often require large quantities of these materials, leading to substantial embodied emissions.

In the next section, we explore what’s driving Europe’s new era of rearmament and how the defence spending boom could quietly push climate goals further out of reach.

The drive to rearm Europe

In early 2025, the geopolitical landscape of Europe shifted dramatically. Following the return of Donald Trump to the White House, and his swift suspension of military aid to Ukraine, European governments were jolted into action. With Washington signalling it would no longer act as Europe's security guarantor, EU and NATO leaders began ramping up defence budgets at a scale not seen since the Cold War.

This collective shift marks a turning point. What was once seen as politically unpopular - heavy military investment - is now being fast-tracked in capitals from Berlin to Brussels. And underpinning much of this shift is NATO’s 2% of GDP target, which has evolved from a long-standing guideline into a new minimum threshold for member states.

The strategic rationale is clear: Europe wants to bolster deterrence, reduce its dependence on the US, and prepare for long-term instability on its eastern flank. But in doing so, defence is rapidly becoming one of the fastest-growing categories of government spending, outpacing health, climate, or social investments in several countries.

In the next section, we take a closer look at what this surge in spending could mean for greenhouse gas emissions, and provide new data that quantifies the scale of Europe’s growing military footprint.

Counting the carbon cost EU military emissions

While Section 3 explored the political drivers and scale of Europe’s rearmament plans, here we turn to a different question: what will this military build-up mean for the climate?

The answer isn’t easy to find. Military emissions are not routinely reported. They’re often buried in government accounts, scattered across defence, energy, and transport categories, or excluded entirely. But that doesn’t mean we can’t estimate the scale of the impact.

To help close this gap in public understanding, Greenly has produced original estimates of military-related emissions tied to Europe’s rearmament drive. Using spending data and published estimates of NATO’s carbon intensity, we model the likely climate cost of NATO and EU defense activities in 2023–2025, and project the impact of the EU’s €800 billion defense sovereignty package.

Methodology

We started with a widely cited 2024 estimate, which found that:

This yields an average emissions intensity of:

This emissions factor includes direct fuel use (from jets, tanks, ships), emissions from military bases and infrastructure, and upstream emissions from equipment production and logistics. We applied this consistent ratio to model the impact of:

- Total NATO military spending in 2024

- EU NATO member military budgets (2024 and 2025)

- The EU’s new €800 billion defence sovereignty package

NATO: Emissions rising alongside budgets

In 2024, NATO’s total military spending reached an estimated $1.47 trillion – a sharp increase from the previous year’s $1.34 trillion. Using the same emissions ratio from 2023 (174 Mt CO₂e per $1 trillion spent) we can estimate the approximate associated emissions:

| Year | NATO Military Spending (USD) | Estimated Emissions (Mt CO₂e) |

|---|---|---|

2023 |

$1.34 trillion | 233 Mt CO₂e |

2024 |

$1.47 trillion (est.) | 256 Mt CO₂e (est.) |

In 2024, NATO’s total military spending reached an estimated $1.47 trillion, up from $1.34 trillion in 2023. This represents a 9.87% increase in military expenditure year-on-year.

Applying the emissions intensity ratio of 174 million tonnes of CO₂e per $1 trillion spent, we estimate that NATO's military activities in 2024 generated approximately 256 million tonnes of CO₂e. This is an increase of 23 million tonnes compared to 2023.

This surge in emissions has been driven by more countries hitting or exceeding NATO’s 2% GDP target for defense spending, which has increasingly been framed as a floor, not a ceiling.

EU NATO members: a growing share of military emissions

Of NATO’s total, around $457 billion was spent by the 23 EU member countries in 2024 - up 11.7% from 2023. With commitments already in place to push this further in 2025, emissions will follow suit. To estimate the carbon impact, we applied the same emissions intensity ratio used earlier - 174 million tonnes of CO₂e per $1 trillion spent.

2024 calculation:

0.457 × 174 = ~79.5 Mt CO₂e

2025 projection:

The European Council projects that defence spending will reach 2.04% of the combined GDP of EU NATO countries in 2025. Based on an estimated combined GDP of $22.84 trillion USD, this translates to approximately $466.1 billion in military expenditure - a figure also referenced in Le Monde’s coverage of the EU's rearmament plans.

Applying our emissions ratio of 174 Mt CO₂e per $1 trillion spent, we estimate:

| Year | EU NATO Military Spending (USD) | Estimated Emissions (Mt CO₂e) |

|---|---|---|

2024 |

$457 billion | ~79.5 Mt CO₂e |

2025 |

$466.1 billion (proj.) | ~81.1 Mt CO₂e |

These figures represent a substantial hidden share of EU emissions, yet defence remains largely excluded from EU climate policies like the Fit for 55 package or national carbon budgets.

The €800 billion question: emissions from Europe’s defence package

The package includes:

While the strategic and political rationale has been made clear, the environmental impact of this €800 billion package has not been publicly quantified, despite its likely substantial carbon footprint.

To estimate this, we used Greenly’s emissions ratio of 174 million tonnes of CO₂e per $1 trillion USD in military spending – derived from NATO’s 2023 emissions and budget data.

Converted at an exchange rate of €1 = $1.08, the €800 billion package equals approximately $864 billion USD, or 0.864 trillion USD. Applying the emissions ratio:

| Initiative | Budget | Estimated Emissions (Mt CO₂e) |

|---|---|---|

EU Defence Sovereignty Package |

€800bn / ~$864bn USD | ~150.3 Mt CO₂e |

Why it matters

At a time when civilian sectors are being pushed to decarbonise, the military sector is quietly moving in the opposite direction.

Yet these emissions are rarely reported. They’re not capped. They’re not taxed. And they’re barely discussed.

This is just one initiative. When taken together with broader NATO and EU defence spending increases, the climate cost of rearmament could seriously undermine global environmental ambitions.

European officials have begun to acknowledge this tension. A recent review by the European Defence Agency (EDA) found that fewer than 40% of EU militaries have any green procurement policy in place for lower-carbon equipment purchases. Even when such policies exist, they are often limited in scope – “green” may refer to noise or pollution controls rather than lifecycle CO₂ emissions.

As Europe ramps up arms production, bases, and logistics networks, this lack of environmental oversight risks locking in decades of carbon-intensive infrastructure and equipment. Joint research by peace and climate organisations warns that, without urgent action to green military procurement and manufacturing, the rearmament drive could directly undermine the EU’s climate targets – including its legally binding Fit for 55 goals.

The climate opportunity cost of rearmament

In 2023, NATO members collectively spent approximately $1.34 trillion on military expenditures. This figure is staggering when juxtaposed with the long-standing climate finance commitment of $100 billion annually to assist developing countries in addressing climate change - a target that was only met in 2022, two years later than promised.

The European Union's €800 billion defense package further underscores this disparity. To put this sum in context, it could alternatively fund:

These comparisons highlight the scale of missed opportunity. As the Transnational Institute put it:

In other words, there is a dangerous feedback loop at play: militarisation worsens climate change, which in turn breeds further conflict. Some policy experts are now calling for a new approach – one of “sustainable security” – where climate and defence priorities are balanced rather than placed in competition.

Can we decarbonise Europe’s defence sector?

While cutting emissions from tanks and warships might seem impossible, experts agree: militaries can and must decarbonise, especially as they become larger emitters in a warming, unstable world.

But the window for action is narrowing.

What would decarbonising the military look like?

Key steps include:

Many of these are technically feasible. The challenge is political will.

Some steps were taken — but momentum may be stalling

But 2025 presents a new challenge

These modest gains are now at risk. The return of Donald Trump to the White House has shifted the global security focus, and with it, the political space for climate-military action is shrinking. Trump’s past record shows little concern for climate policy, and the U.S. military is unlikely to remain engaged on decarbonisation under his leadership.

What needs to happen

If Europe is serious about climate leadership, it must act now to prevent defence from becoming a blind spot. That means:

- Enshrining military emissions disclosure into EU climate law

- Creating binding targets and timelines for defence sector decarbonisation

- Ensuring transparency in defence procurement, including emissions data

- Launching a dedicated green defence innovation fund

- Using part of the EU’s defence budget to scale sustainable energy and infrastructure within the military