ESG / CSR

Industries

Why sewage pollution is becoming an ecological issue

Clean water is something most of us rarely think twice about - we turn on the tap, swim in lakes, or walk along beaches without wondering what might be lurking beneath the surface. But mounting evidence is forcing us to confront a murkier reality: our rivers, seas, and waterways are increasingly being polluted by untreated sewage.

Years of underinvestment, aging infrastructure, and weakened regulation have pushed sewage systems to breaking point, and in countries like the UK, the consequences are becoming impossible to ignore. From closed beaches to foul-smelling rivers, the impact is now visible to communities across the country.

In this article, we’ll explore why sewage pollution is such a growing concern, what’s behind the problem, and why England in particular is facing mounting criticism over the state of its waterways.

What is sewage, and how is it treated?

Sewage is any wastewater that comes from households, businesses, and industries. This includes everything from toilet flushes and sink water to wastewater from showers, washing machines, and dishwashers. In many areas, especially those with combined sewer systems, surface water - including rainwater runoff from roads and gutters - is also channelled into the sewage system, carrying oil, litter, heavy metals, and other contaminants.

The sewage treatment process

In most urban areas, sewage from homes and businesses is carried through a public foul sewer to a sewage treatment plant, also referred to as a sewage treatment works, where it undergoes a series of treatment stages before being discharged into the environment. The process is designed to remove waste products, reduce organic pollution, and eliminate harmful microbes:

Step 1: Preliminary treatment Solid matter like sanitary products, cotton buds, plastics, wipes, and debris are screened out to prevent damage to machinery and reduce blockages.

Step 2: Primary treatment The wastewater is held in settling tanks (also known as settlement tanks), where heavier solids (like food waste) sink to the bottom (forming sludge) and lighter materials like oils and grease float to the top and are skimmed off.

Step 3: Secondary treatment Also known as the biological stage of treatment, this process uses bacteria and microorganisms to break down dissolved and suspended organic matter. It’s often carried out in aeration tanks that supply oxygen to encourage microbial activity.

Step 4: Tertiary treatment This final stage focuses on removing contaminants that earlier stages may have missed, including nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which contribute to algal blooms, as well as harmful pathogens. Techniques often involve filtration, UV disinfection, or chemical treatment.

In rural areas without access to the mains sewer (the public sewer system), individual properties often rely on septic tanks. These are small-scale systems that separate solids from liquids and allow partial treatment on site. However, without regular maintenance or proper siting, septic tanks can leak pollutants into the surrounding soil and groundwater.

After treatment, the leftover sludge from the primary and secondary stages undergoes further treatment to make it safe for disposal or reuse. Depending on the facility, it may be digested, composted, incinerated, used as fertiliser in agriculture, or sent to landfill.

What causes sewage pollution?

Water pollution from sewage doesn’t happen by accident, it’s the result of outdated infrastructure, limited oversight, and a chronic lack of investment. In many parts of the world, untreated or poorly treated sewage is discharged directly into rivers, lakes, and seas, harming ecosystems and putting public health at risk.

Did you know? Over 80% of global wastewater is released into the environment without adequate treatment, according to UN Water.

Here are the key reasons why sewage pollution continues to be such a widespread problem:

1. Outdated and overburdened infrastructure

Many sewage systems still rely on ageing networks of pipes and drains built in the 19th or early 20th century, long before current population sizes and urban expansion.

In the UK, for example, much of the sewage infrastructure dates back to the Victorian era.

These older systems often combine wastewater and stormwater in the same pipes, known as combined sewer systems. During heavy rainfall, they quickly become overwhelmed and are forced to discharge excess sewage into nearby rivers or seas to prevent urban flooding — something referred to as combined sewer overflows (CSOs).

Without major upgrades or system separation, many countries are stuck with systems that simply cannot cope with today’s demands.

2. Inadequate or missing sewage treatment

Even where sewer networks exist, many sewage treatment plants are poorly maintained, under-capacity, or simply non-existent:

- In some regions, especially in low-income countries, there may be no centralised sewage treatment works at all.

- In others, treatment facilities may exist but are not functioning properly due to poor maintenance or lack of staff and funding.

- During peak usage or after storms, many facilities are forced to bypass treatment stages, discharging raw or partially treated sewage into natural water bodies.

According to the World Health Organization, around 46% of the global population lacks access to safely managed sanitation systems.

3. Dumping from ships and cruise liners

Sewage pollution isn’t just a land-based problem. Maritime sewage dumping is a major contributor to coastal water contamination.

While international regulations (like MARPOL Annex IV) prohibit sewage discharge within a certain distance from shore, enforcement is patchy, especially in waters where oversight is limited.

Cruise ships, in particular, are a major source. With an estimated 20 million people sailing annually, these vessels generate over 11 billion litres of sewage each year — not all of which is properly treated before discharge.

4. Underfunding and lack of political priority

Sanitation infrastructure is rarely a headline-grabbing issue and often falls by the wayside when it comes to government budgets and environmental priorities.

In the United States, for example, only $6 million was allocated between 2005 and 2019 to deal specifically with ocean-based sewage pollution.

In many countries, funds are diverted to more visible environmental challenges, like plastic waste or air pollution — despite the public health and ecological risks posed by untreated sewage.

Without sustained political will and financial support, the problem continues to fester.

5. Gaps in scientific research

Finally, sewage pollution has long been under-researched compared to other environmental threats.

While the effects of plastic pollution and oil spills are well documented, the long-term ecological impacts of sewage — such as hormonal disruption, oxygen depletion, and microbial resistance — have not been studied in the same depth.

This lack of data makes it harder to raise awareness, secure funding, or make better policy decisions.

What are the major impacts of sewage pollution?

Sewage pollution has far-reaching consequences that go well beyond unpleasant smells and murky waters. From triggering harmful algal blooms to contaminating food chains and spreading disease, the discharge of untreated or poorly treated wastewater into natural ecosystems can devastate both the environment and the communities that depend on it.

Environmental damage:

1. Eutrophication and algal blooms

One of the most immediate environmental effects of sewage pollution is eutrophication — the excessive buildup of nutrients in a water body, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus. These nutrients stimulate rapid algae and plant growth, often leading to what are known as algal blooms.

When algae grow in dense layers on the water’s surface, they block out sunlight, suffocating the aquatic plants below. As these plants and algae die, they are broken down by bacteria — a process that consumes large amounts of oxygen.

The resulting oxygen depletion (hypoxia) creates “dead zones” where fish, invertebrates, and other aquatic life can no longer survive.

Some algal blooms, such as those caused by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), also produce toxins that are dangerous to fish, birds, domestic animals, and even humans.

2. Disruption of aquatic food chains

Freshwater insects, which play a critical role in river and stream ecosystems, are particularly sensitive to low oxygen levels. Their decline can ripple through the food web:

- Fish species that rely on insects for food may starve or migrate elsewhere.

- Bird species that feed on aquatic life may also be affected.

- In extreme cases, the entire food chain can collapse, leaving a degraded ecosystem behind.

3. Vulnerability of sensitive habitats

Some ecosystems are especially susceptible to the contaminants found in sewage:

- Coral reefs can be smothered by algal growth and weakened by nutrient imbalances, leaving them more vulnerable to bleaching and disease.

- Mangroves and salt marshes — key coastal buffer zones — may suffer reduced biodiversity and productivity.

- Estuaries, where rivers meet the sea, are often hotspots for sewage discharge and can experience long-term degradation if pollution is persistent.

These ecosystems are not only biologically rich, they also provide vital services like coastal protection, carbon storage, and water filtration. Their loss has knock-on effects for both nature and people.

Chemical contamination and disease

Sewage doesn’t just contain organic waste. It also carries a cocktail of industrial and household chemicals, pharmaceutical residues, and pathogens:

In areas where untreated sewage enters water supplies used for drinking, bathing, or agriculture, the consequences can be deadly.

Impact on coastal regions and vulnerable communities

The effects of sewage pollution are not evenly distributed. Coastal communities, river-based settlements, and low-income regions often bear the brunt of the problem:

These communities are often excluded from decision-making and receive little support in addressing the root causes of pollution. As a result, sewage pollution not only becomes an environmental issue, but it's also a question of environmental justice.

Where is sewage pollution a problem?

Sewage pollution is a global issue, but it’s often most severe in regions without adequate sanitation infrastructure. In many developing countries, large volumes of wastewater are discharged untreated into rivers, lakes, and coastal waters due to limited funding, rapid urbanisation, and lack of access to modern sewage systems.

According to the UN, in some of the world's least developed countries, over 95% of wastewater is released into the environment without any treatment. In India, for example, less than 30% of sewage generated in urban areas is effectively treated, leading to widespread contamination of rivers like the Ganges. Similarly, in Nigeria, only 5.3% of urban households are connected to a sewer system, posing a risk to human health and contributing to high levels of waterborne disease.

Why is sewage an issue in England?

Dozens of popular beaches were forced to close again during the summer of 2024 due to unsafe levels of contamination and poor water quality, prompting widespread public anger and renewed scrutiny of how England’s water system is managed.

What’s especially striking is how poorly England is performing compared to other parts of the UK. According to The Rivers Trust, not a single river in England currently meets “good” ecological status overall. Only 15% of river stretches qualify as “good” - compared to over 64% in Scotland, where water remains publicly managed. In Wales, the figure is 40%. Across Europe, the average is 37%.

The contrast reflects both environmental pressures and governance choices. Critics argue that England’s privatised water model, unique within the UK, has allowed companies to prioritise shareholder returns over long-term environmental investment.

To understand how the situation got this bad, it helps to look at how the UK’s sewage system developed, and why it’s now struggling to cope.

1. A system built for the 19th century

England’s sewer network was never designed for a modern population. London’s sewer system was built in the 19th century by engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette. When it officially opened in 1865, it included over 1,100 miles of sewer pipes. Other cities soon followed, and by 1945 there were around 1,400 local sewage providers.

These were then merged into ten regional water authorities in 1973. But by the mid-1980s, public investment had already begun to fall. Funding dropped from £3.5 billion in 1974 to just £1.8 billion in 1985.

Then, in 1989, the system was privatised. Today, 32 private companies manage water and sewage services in England and Wales.

2. The consequences of privatisation

Privatisation was supposed to bring in investment and improve efficiency. But in practice, it created a conflict: water companies were expected to generate profit, attract shareholders, and deliver a reliable public service, all while maintaining ageing infrastructure.

As maintenance costs have grown and climate pressures have increased, many companies have struggled to keep up without passing costs onto customers or cutting corners on long-term upgrades.

Climate change has added pressure, with more frequent and intense rainfall overloading combined sewer systems. When overwhelmed, these systems discharge untreated sewage into rivers and seas via storm overflows.

These discharges are legal under certain conditions, but regulators have found that the rules are often abused:

- Southern Water: fined £90 million in 2021 after illegally dumping 21 billion litres of sewage over six years.

- Thames Water: fined £123 million in May 2025 for excessive discharges and unjustified dividends, with over half its treatment plants operating beyond capacity.

3. Deregulation and underfunding

The crisis hasn’t happened in a vacuum. Years of political inaction, regulatory leniency, and underfunding have all contributed to the decline of England’s sewage system. Successive governments have been slow to invest in long-term infrastructure or hold water companies to account, while oversight agencies have faced repeated budget cuts.

During the 2010s, funding for environmental monitoring was significantly reduced, including cuts to programmes designed to detect illegal sewage discharges. Environmental groups have pointed to this period as a turning point in regulatory enforcement, when monitoring capacity dropped just as pollution incidents began to rise.

Critics argue that regulators like Ofwat and the Environment Agency have allowed companies to underinvest in maintenance while continuing to pay out dividends and bonuses, creating a system where financial incentives were not aligned with environmental responsibility.

4. A widespread, systemic issue

The sewage crisis isn’t limited to a few bad apples, it reflects systemic failings across the industry.

In 2022, the Environment Agency launched what it describes as its largest ever criminal investigation into potential breaches of environmental permit conditions by all water and sewerage companies discharging into English waters.

The scale of the inquiry is significant. As of mid-2025, the investigation covers more than 2,200 wastewater treatment works. The agency has reviewed over 35,000 exhibits and compiled more than 1,050 witness statements. The investigation has now entered a new phase, with officers beginning to gather testimony from external witnesses.

While formal outcomes have not yet been announced, early findings suggest that widespread non-compliance may have become routine practice, reinforcing concerns that England’s sewage pollution problem is not the result of isolated mismanagement, but a deeply rooted industry-wide issue.

What’s being done to improve water quality?

1. Government action

After years of public outcry, government and regulatory bodies have started taking more serious action.

A key step was the Storm Overflows Discharge Reduction Plan, introduced under the Environment Act. It legally requires water companies to:

- Improve all storm overflows near bathing waters by 2032

- Improve 75% of overflows near high-priority nature sites by 2032

- Bring all remaining overflows up to standard by 2050

The timeline has been widely criticised as too slow, but it marks a shift toward binding targets.

2. Boosting monitoring and investment

One area of progress is monitoring. In 2016, only 800 overflows were being tracked. By 2021, that had grown to 12,700, and by 2024 it had reached over 14,000. This allows regulators to better track how often and for how long raw sewage is being released.

The Environment Agency has also required companies to submit annual reduction plans, improve how they measure flows at treatment works, and invest in new storm tanks. In total, water companies have pledged over £12 billion in upgrades by 2030, with the government and Ofwat overseeing spending.

3. Legal crackdowns and reforms

Since 2015, the Environment Agency has prosecuted water companies over 56 times, resulting in £141 million in fines. But tougher measures have now been introduced.

In early 2025, the government passed the Water (Special Measures) Act, giving Ofwat powers to freeze executive bonuses and pursue criminal charges against senior management.

By mid-2025, six major firms, including Thames, Southern, and Yorkshire Water, had executive bonuses suspended due to persistent pollution failures.

4. New infrastructure: the Thames Tideway Tunnel

One of the most ambitious projects to tackle overflows is the Thames Tideway Tunnel – a 25 km “super sewer” running beneath London.

Officially opened in May 2025, the tunnel is expected to capture over 95% of sewage overflows into the Thames, preventing around 39 million tonnes of waste from polluting the river annually.

Looking forward

Sewage pollution is a serious and often overlooked environmental issue, affecting not just low-income countries, but wealthy nations as well. In places like the UK, decades of underinvestment, weak regulation, and prioritisation of profits have left systems unable to cope.

Unlike plastic or air pollution, sewage rarely dominates headlines, yet its impact on ecosystems and public health is significant. The growing public backlash is now forcing governments and regulators to respond through stronger oversight, infrastructure upgrades, and greater transparency.

It’s a long overdue shift, and one that’s essential to protect the future of our rivers, seas, and the communities that depend on them.

What about Greenly?

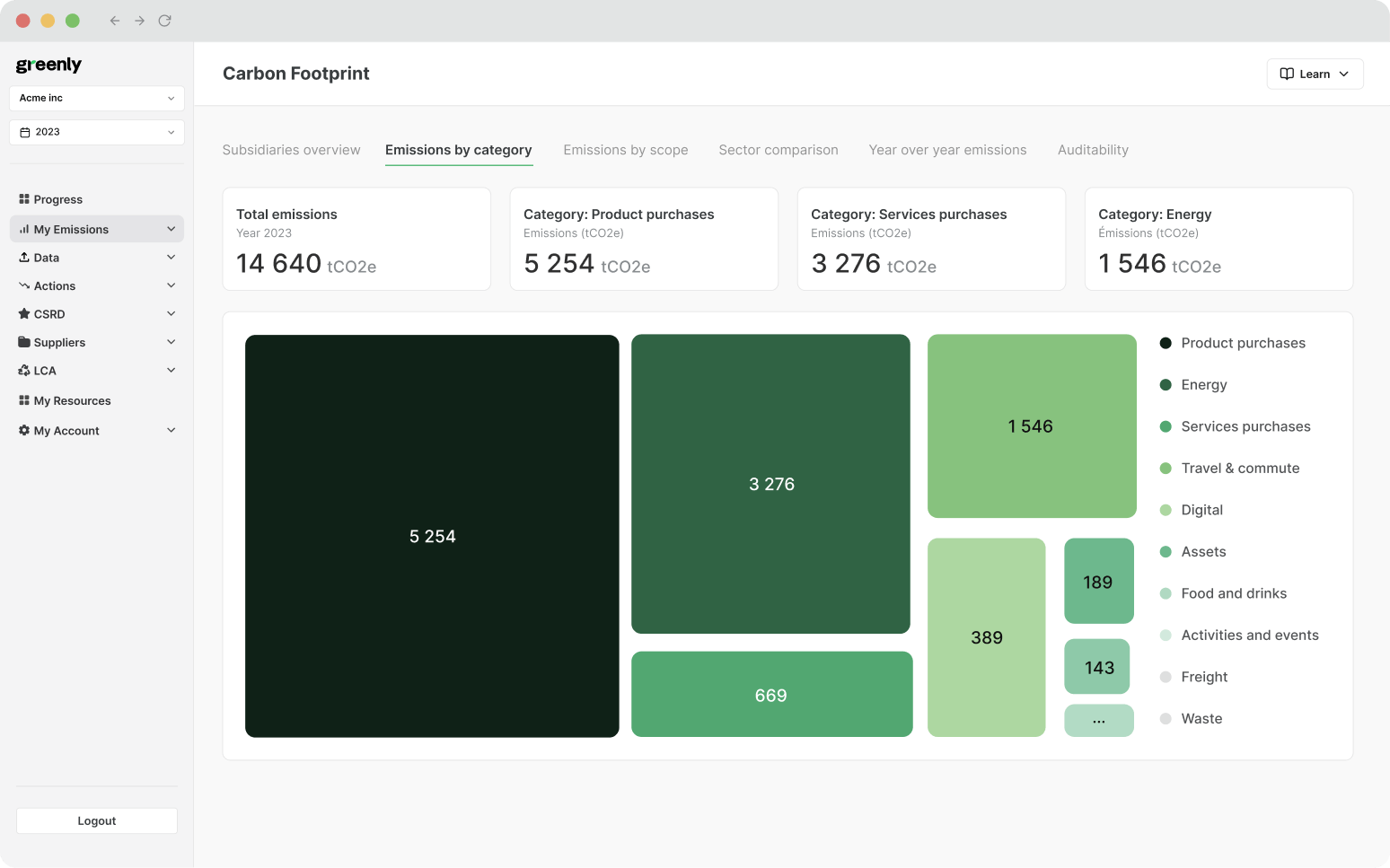

At Greenly, we help companies take control of their environmental impact and build credible, data-driven sustainability strategies. Our suite of carbon management services is designed to make climate action clear, actionable, and aligned with the latest regulatory and market expectations.

Here’s how we can support you:

- Track your emissions: We measure your carbon footprint across Scopes 1, 2 and 3, using real business data to uncover key impact areas.

- Analyse and reduce: Our platform highlights where emissions are highest and offers tailored strategies to reduce them efficiently.

- Manage your supply chain: We provide visibility into supplier emissions and help you build a more sustainable value chain.

- Align with leading standards: We support reporting in line with frameworks such as the GHG Protocol, SBTi, CSRD, and more.

- Improve transparency: Generate robust reports and share your progress with stakeholders, customers, and regulators.

Whether you're just getting started or looking to take your climate strategy to the next level, Greenly gives you the tools and expertise to move forward with confidence. Get in touch today to find out more.