ESG / CSR

Industries

What is the Doomsday Glacier and Why Does it Matter?

If Thwaites were to fall, it wouldn’t just contribute significantly to sea level rise – it could also destabilise the broader West Antarctic Ice Sheet, triggering a chain reaction of ice loss across the region.

In this article, we’ll unpack what the Doomsday Glacier is, why scientists are watching it so closely, and what can be done to slow its retreat.

What is the Doomsday Glacier? A quick overview

The Doomsday Glacier refers to Thwaites Glacier, named after glacial geologist Fredrik T. Thwaites. Located in West Antarctica and forming part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), the glacier has gained its ominous nickname due to the scale of the threat it poses to global sea levels.

Like many glaciers around the world, Thwaites is retreating. But the pace and magnitude of its ice loss are particularly alarming. Each year, it sheds around 50 billion tonnes more ice than it gains through snowfall. And that rate is accelerating, with total ice loss having doubled over the past three decades alone.

Why is the Doomsday Glacier a threat?

Like many glaciers, Thwaites loses ice through both melting and calving, with meltwater and ice flowing directly into the ocean. The more it retreats, the greater its contribution to rising global sea levels.

But the concern doesn’t stop there. Thwaites acts as a kind of natural dam, holding back neighbouring glaciers like Pine Island and Haynes. If it falls, it could destabilise these ice masses too, unleashing a chain reaction of retreat across the WAIS. In the worst-case scenario, this broader collapse could release enough ice to add up to 1.5 metres to global sea levels over time.

Thwaites is already showing signs of severe instability. It’s currently experiencing the most dramatic changes of any ice–ocean system in Antarctica, with one of the fastest retreat rates and least stable ice shelves on the continent. This is why it has become such a focal point for climate scientists and the media.

What’s happening to the Doomsday Glacier?

Thwaites Glacier is currently buttressed by a floating ice shelf – the Thwaites Ice Shelf – which extends into the Amundsen Sea. This ice shelf plays a critical role: it acts like a natural dam, holding the glacier in place and shielding it from the direct impact of warmer ocean waters.

But this protective barrier is rapidly weakening. Rising ocean temperatures are melting the ice from below, thinning the shelf and making it increasingly unstable. Scientists warn that parts of the ice shelf could collapse within the next decade.

If that happens, Thwaites would lose one of its last stabilising forces, leading to a faster flow of ice into the sea. Without this support, the glacier’s slide into the ocean would accelerate, increasing its contribution to sea level rise. In the short term, this could push its share of annual sea level rise from 4% to 5%. Over the longer term, the retreat could accelerate dramatically, setting off centuries of ice loss with irreversible consequences.

What have scientists observed?

Scientists have been monitoring Thwaites Glacier for several decades and have recorded two key warning signs: the glacier is flowing faster, and its grounding line is retreating. Both are strong indicators of growing instability.

Increasing glacial flow

Glacial flow refers to the natural movement of ice from higher elevations toward the ocean, driven by gravity. Thwaites is what’s known as an outlet glacier, meaning it channels ice from the interior of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet directly into the sea. It also contains some of the fastest flowing grounded ice in Antarctica, making it a critical point of concern for scientists tracking ice loss and sea level rise.

This flow is what forms floating ice shelves. In Thwaites’ case, the ice shelf extends around 120 kilometres across, towering up to 40 metres above sea level and plunging 200 metres below the surface. A notable feature of Thwaites is its ice tongue - a long, narrow sheet of ice projecting out from the glacier into the sea, formed as the glacier flows rapidly into the ocean.

But when the glacier flows too quickly, the ice shelf struggles to keep up. Ice breaks away faster than it can be replaced, weakening the entire structure. This is a major concern, since the ice shelf acts as a brace, helping to stabilise the glacier and slow its collapse.

Retreating grounding line

The grounding line marks the point where the glacier lifts off the land and begins to float on the ocean. When this line retreats inland, it exposes more of the glacier’s underside to warm ocean water, creating a cavity beneath the ice shelf and reducing its structural support.

In recent years, scientists have observed the rapid retreat of Thwaites’ grounding line, leading to the formation of a vast under-ice cavern. Relatively warm ocean water is now infiltrating these gaps between the bedrock and the glacier, accelerating melting from below.

A NASA-led study in 2021 revealed the scale of this underwater cavity: nearly 300 metres tall and covering an area two-thirds the size of Manhattan, it once held an estimated 14 billion tonnes of ice.

Perhaps most alarming was how quickly it formed – in just three years. The rapid melt raises serious concerns about the glacier becoming unmoored from the bedrock below. Since the underlying rock helps anchor and stabilise the glacier, its loss could mark a critical tipping point.

What have recent studies shown?

Recent research has revealed a more nuanced understanding of the forces shaping Thwaites Glacier. While the glacier is still retreating, one surprising finding offers a small degree of reassurance: the rate of melting at its base is slower than previously expected. This suggests that, in some areas, the glacier may be showing more resilience to warming than scientists had initially feared.

However, this cautious optimism is offset by other discoveries that paint a more troubling picture.

Melting in these structurally weak zones is occurring at a much faster rate. This is especially concerning because it allows warmer water to penetrate deeper into the glacier system, undermining the ice shelf from within and increasing the risk of collapse.

The contrast between slower melting at the base and rapid melting in more fractured areas highlights just how complex and precarious Thwaites' situation is - and underscores the deep uncertainty scientists face when trying to predict its future behaviour.

So while some findings offer a glimmer of hope, the broader outlook remains deeply concerning.

Why is the Doomsday Glacier melting?

This warming is now destabilising glaciers across Antarctica. In the case of Thwaites, several interconnected factors are accelerating its retreat:

What is the impact of melting glaciers?

The collapse of Thwaites Glacier wouldn’t just raise sea levels, it would send shockwaves through global climate systems, ecosystems, and human communities. Here we explore some of the most severe consequences:

Sea level rise

Glacier destabilisation

Ocean circulation

Marine ecosystems

Weather patterns

Greenhouse gases

Scientific loss

What's the outlook for the Doomsday Glacier?

Thwaites Glacier is retreating fast, and scientists are worried.

Research shows that its ice shelf could collapse within the next decade, removing one of the last barriers slowing the glacier’s flow. This would accelerate its retreat and increase its contribution to sea level rise.

Can we prevent it from melting?

The biggest lever we have is reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

As long as we continue burning fossil fuels, global temperatures will rise and with them, the pace of glacier melt. Rapid decarbonisation is essential to slow warming and limit further destabilisation.

But even if we reach net zero, some degree of melting is now inevitable due to existing levels of warming. This is why adaptation planning and scientific modelling are just as important as mitigation.

Why research still matters

Ongoing studies help us predict what’s next and prepare.

Glaciers like Thwaites are complex systems, and scientists need accurate data to forecast their behaviour. Research efforts like the UK–US-led International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration - involving scientists from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and other leading institutions - are using satellite imagery, radar, and under-ice robotics to map the glacier’s structure and monitor how it is changing in real time.

This joint research programme aims to improve understanding of the processes affecting ice sheet stability and to predict, with greater certainty, the future contribution of Thwaites Glacier to sea-level rise. By studying how the glacier is behaving now and how it has responded to environmental change in the past, scientists can develop more accurate models to inform global climate planning.

These models help us:

- Anticipate how quickly sea levels might rise

- Understand regional and global climate impacts

- Inform resilience strategies to adapt to future changes

What about Greenly?

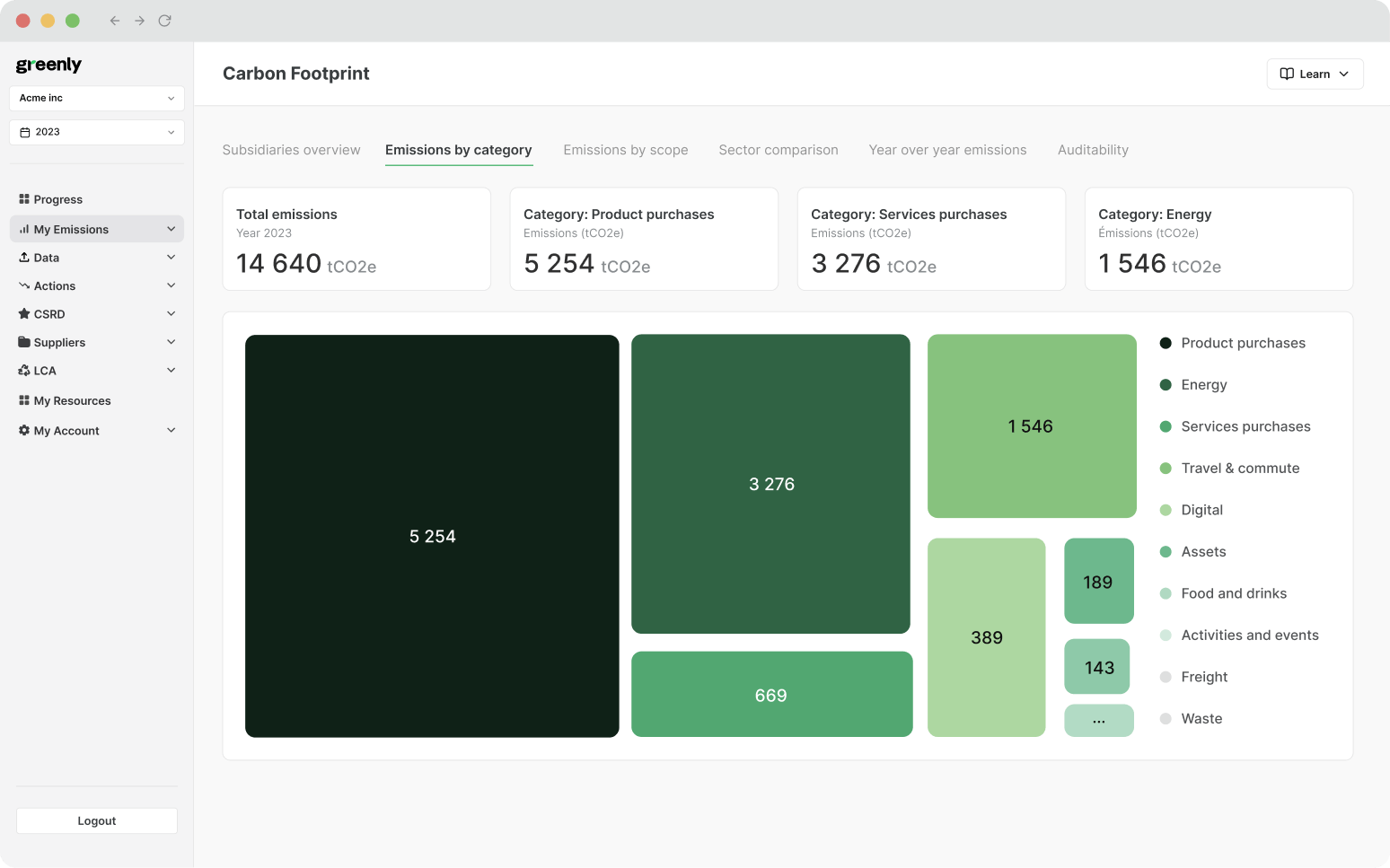

At Greenly, we help companies take meaningful climate action, including reducing the emissions that contribute to the melting of glaciers like Thwaites.

Our suite of carbon management services is designed to help companies track, analyse, and reduce their environmental impact, making sustainability both actionable and achievable.

With Greenly, your business can:

- Measure and monitor Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions using real-time data

- Identify high-emission activities and implement targeted reduction strategies

- Access decarbonisation pathways aligned with science-based targets

- Improve supply chain sustainability through vetted low-carbon suppliers

- Obtain certifications and build investor confidence with credible climate reporting

Whether you're just getting started or looking to lead on climate, Greenly provides the tools and support to make your impact count.

Ready to reduce your footprint? Get in touch with our team today.