ESG / CSR

Industries

What is El Niño and why does it matter?

As El Niño took hold, 2023 became one of the hottest years on record, and its ripple effects have triggered extreme weather events worldwide.

However, with El Niño now officially ending, the world is preparing for a potential transition to La Niña, which could bring a new set of climate impacts.

In this article, we'll explore what El Niño is, how it interacts with climate change, and the potential global consequences.

What is El Niño?

El Niño was first observed by South American fishermen, who noticed a periodic warming of the ocean waters around Christmas time.

They named it El Niño de Navidad - meaning "the Christ Child" - because it often peaks around December. Though initially known only in the Pacific region, scientists have since discovered that El Niño’s influence extends well beyond, affecting global weather patterns.

Its impacts range from intense droughts in some areas to increased rainfall and flooding in others. The most recent El Niño, which began in 2023, played a major role in fueling record-high global temperatures and extreme weather worldwide.

Although El Niño is now coming to an end, its aftereffects will continue to shape global weather, and the world is now preparing for a likely transition to La Niña.

El Niño and La Niña: a constant state of fluctuation

El Niño means "the Little Boy" or "the Christ Child" in Spanish, it is just one phase of a broader climate phenomenon known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which sees the Earth’s climate system oscillate between two opposite extremes: El Niño and La Niña.

La Niña, meaning "the Little Girl," represents the cooler counterpart to El Niño. This cycle typically spans 3 to 7 years, with 5 years being the average.

The ENSO cycle plays a key role in shaping weather patterns across the globe, leading to fluctuations between warm (El Niño) and cool (La Niña) oceanic conditions in the Pacific.

La Niña is the counterpart to El Niño and represents a period of unusually cool sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific. During La Niña events, temperatures can drop 3 to 5 degrees Celsius below the average, often resulting in cooler, drier weather in the tropical eastern Pacific region. However, much like El Niño, La Niña’s impacts are far-reaching, with global consequences such as increased rainfall in some regions and drought in others.

The cycle’s timing is also critical. El Niño and La Niña events generally form between March and June but reach their peak between December and April, when their effects on global weather are most pronounced.

El Niño typically lasts 9 to 12 months, although some episodes can extend for 3 to 4 years, as seen in recent decades. La Niña, on the other hand, tends to last longer, usually persisting for 1 to 3 years.

It’s also important to note that in some years, neutral conditions prevail, where sea surface temperatures in the Pacific are closer to the long-term average. In fact, about half of all years fall into this "neutral" category, where neither El Niño nor La Niña dominates the climate system.

What causes El Niño?

ENSO represents a periodic fluctuation in sea surface temperatures and atmospheric pressure across the equatorial Pacific, driving changes in global weather systems.

This oscillation between warm (El Niño), cool (La Niña), and neutral phases affects tropical rainfall, wind patterns, and ocean currents, with significant impacts on climate worldwide.

Neutral state

Under normal (neutral) conditions, the tropical Pacific Ocean is characterised by stable trade winds that blow from east to west along the equator.

These trade winds push the sun-warmed surface waters from the cooler eastern Pacific (near South America) toward the western Pacific Ocean (near Indonesia and Australia). As a result, sea surface temperatures in the western Pacific become significantly warmer - by 8 to 10 degrees Celsius - compared to the eastern Pacific.

This temperature difference drives atmospheric circulation. The warmer waters in the west generate low-pressure zones and create hot, humid conditions, leading to frequent rainfall in the western Pacific. Meanwhile, the cooler waters in the eastern Pacific maintain higher air pressure, creating drier and cooler weather along the western coast of South America. This balance of wind and ocean currents is the neutral state of the ENSO cycle.

El Niño

During an El Niño event, this equilibrium is disrupted.

The trade winds, which normally push warm water westward, weaken or even reverse, blowing in an easterly direction. This allows the warm water that is typically confined to the western Pacific to spread eastward toward the central and eastern parts of the ocean. As a result, sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific rise dramatically, and the usual temperature contrast between the east and west Pacific is diminished.

The intensity of El Niño events can vary significantly. In weaker El Niño episodes, sea surface temperature increases may be relatively modest, around 2–3 °C, leading to only moderate local effects on weather patterns. However, during stronger events, sea surface temperatures can increase by as much as 8–10 °C, triggering far-reaching and often severe climatic changes across the globe.

This shift in ocean temperatures triggers a chain reaction in the atmosphere. Higher air pressure builds over the western Pacific (around the Indian Ocean, Indonesia, and Australia), while lower pressure develops over the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. The reversal of these pressure patterns leads to changes in tropical rainfall: drier-than-usual conditions and droughts impact the western Pacific, while wetter, stormier weather affects the eastern Pacific, including the coasts of South America and North America. These altered circulation patterns can result in flooding in some regions and droughts in others, with the intensity of these impacts closely linked to the strength of the El Niño event.

La Niña

In contrast, La Niña represents the cooling phase of the ENSO cycle and occurs when the trade winds intensify rather than weaken.

These stronger winds push the warm surface waters of the western Pacific even further west, allowing colder, nutrient-rich deep ocean water to upwell along the equatorial eastern Pacific, particularly near the western coast of South America. This phenomenon causes the sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific to drop by 3 to 5 degrees Celsius below average.

As the ocean cools, atmospheric patterns shift again. Low pressure dominates the western Pacific, bringing wetter conditions to regions like Southeast Asia and northern Australia. Meanwhile, high pressure strengthens in the eastern Pacific, contributing to drier and cooler weather in South America. The intensified trade winds and cooler ocean temperatures also reduce the likelihood of tropical storm activity in the eastern Pacific while increasing storm activity in other parts of the world, such as the Atlantic basin.

Global impacts of ENSO

El Niño is often linked to increased storm activity and warmer global temperatures, while La Niña tends to cool the planet slightly and enhance the likelihood of hurricanes in the Atlantic.

Both phases of ENSO cause dramatic shifts in rainfall, drought patterns, and storm intensities, influencing weather across continents and affecting ecosystems, agriculture, and economies around the world.

What effects do El Niño and La Niña have on global weather patterns?

El Niño and La Niña are powerful climate phenomena that significantly alter global weather patterns, but their impacts vary greatly depending on geographic location, the intensity of the event, the time of year, and other interacting climate systems. No two El Niño or La Niña events are the same, making them challenging to study and predict. Understanding these phenomena is essential for anticipating extreme weather events and preparing for their impacts.

El Niño

During an El Niño event, the weakening of trade winds allows warm water to move eastward toward the coast of the Americas. This shift causes an array of weather disruptions across the globe:

- Regions such as southern South America, the southern United States, the Horn of Africa, and central Asia experience increased rainfall, often leading to flooding.

- In contrast, dry conditions and severe droughts frequently occur in areas like Australia, Indonesia, and parts of southern Asia. These regions may also face increased wildfire activity due to the lack of precipitation.

- Hurricane activity tends to rise in the central and eastern Pacific due to warmer ocean temperatures, while the risk of hurricanes in the Atlantic decreases, as El Niño suppresses storm formation in the region.

La Niña

La Niña, the colder counterpart to El Niño, typically reverses these effects by enhancing trade winds and pushing warm water further west:

- Wet conditions prevail in regions like Australia, Southeast Asia, southeastern Africa, and northern Brazil, often leading to heavy rainfall and flooding.

- Meanwhile, drier-than-normal conditions are observed in parts of South America (particularly the southern regions), the Gulf Coast of the United States, and parts of southern Africa.

- In North America, winters during La Niña events are typically colder and stormier, especially across the northern United States and Canada, while the southern United States may experience milder, drier conditions.

- La Niña also promotes upwelling - a process where nutrient-rich, cold waters rise to the ocean's surface along the western coast of South America, boosting marine life and benefiting fisheries.

| Region | Impact During El Niño | Impact During La Niña |

|---|---|---|

| North America | Wetter southern U.S.; reduced hurricane activity in the Atlantic | Colder, stormier winters in the northern U.S.; drier in the south |

| South America (North) | Drier in northern regions, reduced rainfall | Increased rainfall in northern Brazil |

| South America (South) | Wetter conditions, increased flooding in southern regions | Drier-than-normal conditions, particularly in southern regions |

| Africa (Horn of Africa) | Increased rainfall, potential for flooding | Drier conditions |

| Africa (Southern) | Drier conditions, drought, and increased wildfire risk | Wetter conditions, flooding in southeastern Africa |

| Australia | Drier conditions, risk of drought and wildfires | Wetter conditions, increased flooding |

| Southeast Asia | Drier, warmer conditions, increased risk of wildfires | Wetter, cooler conditions, increased rainfall |

| East Asia (Central Asia) | Increased rainfall, potential for flooding | Drier conditions |

| Pacific Ocean | Increased hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific | Reduced hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific |

| Atlantic Ocean | Decreased hurricane activity | Increased hurricane activity |

| Europe | Warmer winters, wetter conditions (especially southern Europe) | Colder winters, potential for drier southern conditions |

Southern oscillation and climate change

How climate change might influence ENSO

Since the 1970s, El Niño events have occurred more frequently and lasted longer, raising questions about whether rising global sea surface temperatures are facilitating the development and persistence of these events. The additional heat stored in oceans due to human-induced climate change may be altering normal ocean circulation patterns and amplifying the strength of ENSO cycles.

However, new research highlights the challenges in predicting ENSO events in the context of climate change. According to the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) in Australia, global heating is making historical models of El Niño and La Niña less reliable. Dr. Karl Braganza, BoM’s national manager of climate services, emphasized that while the climate system hasn’t “broken,” the relationships between ENSO and regional weather patterns are becoming less consistent.

For example, in the past, El Niño was strongly associated with warmer and drier conditions in regions like Australia and Indonesia, while La Niña brought cooler and wetter weather. However, these links are becoming more unpredictable as heat builds in the oceans, making the past less useful for forecasting the future.

Dynamical models that consider real-time ocean and atmospheric conditions, including greenhouse gas concentrations, are now more effective than older statistical models based on historical data.

Combined impact of ENSO and climate change

Regardless of how climate change directly affects the ENSO cycle, it is clear that the combination of global warming and ENSO events is exacerbating extreme weather patterns. As temperatures rise globally, ENSO events appear to trigger more severe climatic responses, including intensified storms, droughts, and temperature extremes.

- El Niño now drives heavier rainfall and flooding in regions like southern North America and parts of South America, while worsening droughts in areas such as Australia, Indonesia, and Brazil. The increased energy in the atmosphere, due to warming oceans, magnifies the impacts of these extreme El Niño events.

- La Niña episodes, though associated with cooler global temperatures, can still lead to more intense cold air outbreaks in North America, boost hurricane activity in the Atlantic, and cause heavier rainfall in Southeast Asia and northern Australia. The unpredictable shifts in these patterns add further complexity to managing extreme weather risks.

Dr. Braganza noted that forecasts for ENSO events must now account for these uncertainties. For example, the 2023 El Niño initially brought hot, dry conditions to Australia, but unexpectedly, torrential rains followed in December and January, highlighting the growing unpredictability of ENSO’s effects under climate change.

The future of ENSO in a warming world

Global meteorological agencies are adapting their forecasting models to reflect the increasing unpredictability of El Niño and La Niña in a warming world. Dynamical models, such as BoM’s ACCESS-S, which use real-time ocean and atmosphere observations, are now more reliable than historical data alone. These models offer probabilistic forecasts, which help communities assess the likelihood of different weather outcomes, allowing them to better hedge their risks and prepare for extreme weather.

As the Earth continues to warm, the interplay between ENSO and climate change is likely to lead to even more intense and unpredictable weather patterns. The 2023-2024 El Niño event pushed global temperatures to record highs, and future El Niño and La Niña events are expected to continue exacerbating weather extremes, especially in regions vulnerable to their impacts.

The end of El Niño

The 2023-2024 El Niño cycle, which began in June 2023 and contributed to some of the hottest global temperatures on record, has now officially ended. In June 2024, both the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirmed that El Niño conditions are no longer present.

As the cycle ends, scientists are now predicting a possible transition to La Niña conditions, which could bring its own set of global impacts.

Impacts of the 2023-2024 El Niño

The El Niño event of 2023-2024 had profound effects on global weather patterns, pushing temperatures and extreme weather events to new highs:

- Global temperatures soared, contributing to record-breaking heatwaves in many regions, particularly in Europe and North America. In 2023, every month from June onward was the hottest on record, with global average temperatures rising sharply due to a combination of El Niño and long-term climate change.

- Searing heatwaves affected countries around the world, with temperatures well above average in parts of Europe, Asia, and the United States. In southern Europe, countries like Spain, Italy, and Greece faced hotter summers with higher-than-normal temperatures, intensifying the ongoing risks of drought and wildfires.

- In contrast, Australia and Indonesia faced droughts and an increased risk of wildfires due to the hotter, drier conditions typically associated with El Niño.

- East Africa experienced heavier rainfall, leading to flooding in some areas. The Pacific region also faced an increase in tropical cyclones, as warmer sea surface temperatures fueled storm activity across the central and eastern Pacific.

- North America saw a mix of weather extremes. The southern U.S. experienced wetter-than-normal conditions, while parts of the northern U.S. faced milder winter temperatures and hotter-than-average summers.

La Niña looms for 2024

As El Niño ends, attention is now shifting toward a possible La Niña event, which is predicted to develop later in 2024. The WMO forecasts at least a 60 % chance of La Niña conditions developing by the end of 2024.

- La Niña typically brings cooler sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific, which could lead to a temporary dip in global temperatures. However, given the high baseline temperatures caused by climate change, this cooling effect may be less pronounced.

- La Niña could trigger wetter conditions in regions like Australia, Southeast Asia, and Southeastern Africa, while parts of South America and the southern U.S. may experience drier-than-normal conditions.

- Hurricane activity in the Atlantic Ocean is expected to increase, as La Niña generally favors more frequent and intense storms in this region due to reduced wind shear, which would otherwise suppress storm formation.

The future outlook

Furthermore, La Niña’s cooling effect will likely be modest, as the planet's overall warming trend continues. The impact of La Niña will be closely monitored, particularly in regions vulnerable to its effects, such as Southeast Asia and the Atlantic hurricane basin.

It is clear that while El Niño is over, the world remains on edge as La Niña takes center stage.

The combined effects of these climate phenomena with global warming will continue to shape weather patterns worldwide, reinforcing the need for early warnings and preparedness.

Round up

Even though the science is not clear on whether or not climate change is impacting the El Niño Southern Oscillation cycle, what is clear is that El Niño and La Niña have the potential to exacerbate the impacts of global warming.

We’re now heading into another El Niño period, and even though the most extreme effects are not expected to be felt until 2024, the combination of climate change and El Niño means that we are entering uncharted territory.

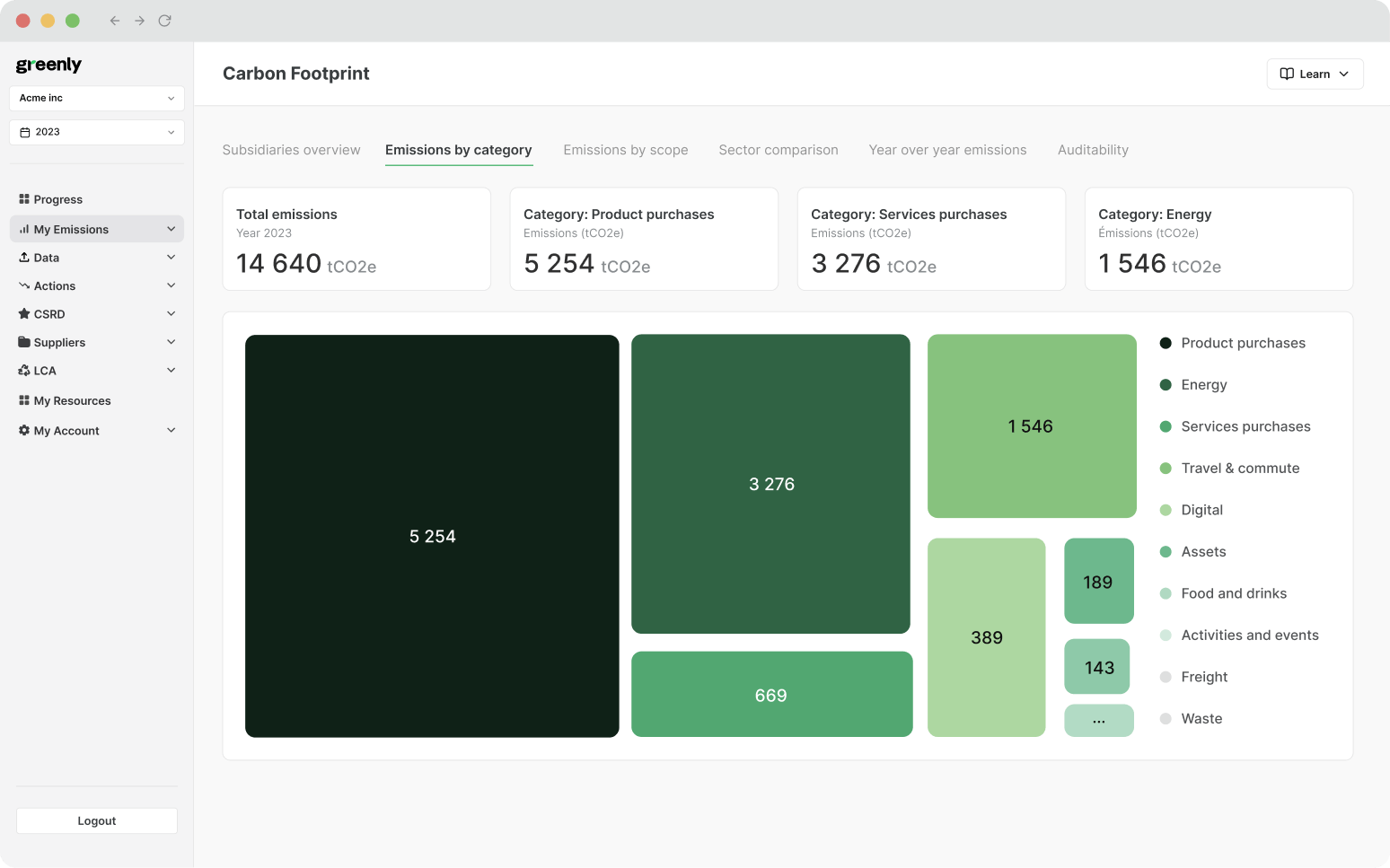

How Greenly can help your business address climate change challenges

As climate change continues to disrupt weather patterns and intensify global environmental challenges, businesses have a critical role to play in driving meaningful action. At Greenly, we empower companies to navigate the complexities of sustainability, helping them reduce their carbon footprint and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Carbon management solutions

Greenly offers a full suite of services designed to help businesses measure, manage, and reduce their carbon emissions, equipping you with the tools to make tangible progress toward your sustainability goals:

- Measure Your Carbon Emissions: Our advanced platform provides real-time insights into your Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, enabling accurate tracking and reporting of your carbon footprint.

- Custom Reduction Plans: Our team of climate experts works closely with your business to create tailored strategies targeting your most significant emissions sources, ensuring practical and impactful reduction efforts.

- Monitor and Report Progress: Track your progress toward net-zero goals with our intuitive platform, which allows you to monitor, measure, and report on your sustainability efforts in a seamless and transparent manner.

Decarbonising your supply chain

In addition to addressing your company’s direct emissions, Greenly helps you reduce your environmental impact across the entire supply chain. Our tools foster greater transparency, engage your suppliers in sustainability efforts, and guide your business toward low-carbon alternatives, ensuring your climate initiatives reach every aspect of your operations.

Seamless integration for sustainability management

Greenly’s platform integrates effortlessly with your existing business processes, allowing you to track and report on your environmental impact. Whether you're managing ESG targets or navigating complex sustainability data, our platform streamlines the process, allowing you to focus on driving both business growth and environmental responsibility.

Start your journey with Greenly today and take meaningful steps to address the challenges of climate change, making a positive impact on your business, your community, and the world.