Impacts, Risks, and Opportunities (IRO) for CSRD Reporting

In this article, we’ll break down what IROs are, how to identify and assess them, and what CSRD requires in terms of disclosure.

ESG / CSR

Industries

The Loss and Damage Fund is widely seen as one of the most significant outcomes in the history of international climate negotiations. Agreed at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, the fund marked a historic agreement and a major breakthrough after more than three decades of pressure from developing nations.

Its aim? To provide financial support to the world’s most vulnerable countries as they deal with the devastating impacts of climate change – impacts they did little to cause.

Since the concept was first proposed in 1991, progress had been painfully slow, blocked repeatedly by wealthy nations wary of financial liability. But in 2022, momentum shifted. The creation of the fund was hailed as a historic victory for climate justice.

Climate change is no longer a distant threat – it’s a daily reality. From relentless heatwaves and rising sea levels to severe flooding, droughts, and vanishing biodiversity, communities across the globe are feeling the pressure. But while climate change affects everyone, some countries are bearing the brunt far more than others.

These are often developing nations, with limited financial resources, fragile infrastructure, and less capacity to prepare for or recover from climate disasters. And what makes this even more unjust is the fact that these same countries have contributed the least to the problem.

The Loss and Damage Fund was created to acknowledge and address this stark imbalance. It's designed to provide financial assistance to nations dealing with the unavoidable impacts of climate change, whether sudden disasters or slow-onset events that unfold over time, such as sea level rise or permafrost thaw.

The idea behind the Loss and Damage Fund has been around for over three decades, but its journey to becoming a reality has been slow and fraught with resistance.

1991 – The first proposal

The concept of a dedicated fund to address climate-related loss and damage was first introduced by Vanuatu, on behalf of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), during early negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Geneva. These nations were among the first to highlight the injustice of climate change, being highly vulnerable yet least responsible.

2007 – Official recognition, but little progress

It wasn’t until COP13 in Bali (2007) that the term “loss and damage” appeared in official UNFCCC documents. From then on, it became a recurring topic at climate summits, but not one that gained much traction.

2013 – The Warsaw Mechanism

At COP19 in Warsaw, countries agreed to establish the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage (WIM). While this marked progress on paper, the mechanism lacked any financial structure, offering support only in the form of dialogue and technical assistance.

2015 – A cautious nod in the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement (COP21) did include a reference to loss and damage in Article 8, acknowledging it as a distinct area alongside mitigation and adaptation. But once again, the language was carefully worded to avoid any legal or financial obligations for developed nations.

Years of stalled negotiations

In the years that followed, developing countries repeatedly pushed for a proper financing facility. Yet wealthier nations, particularly those historically responsible for the majority of emissions, resisted. Their concern? That financial commitments could be interpreted as an admission of legal liability for the impacts of climate change.

By the time COP27 came around, the frustration among vulnerable nations had reached a tipping point.

COP27, held in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, marked a historic turning point in global climate negotiations.

It was one of the most closely watched and hotly debated topics of the summit. After tense negotiations, and years of resistance from wealthier nations, the deal was struck in the early hours of the final day. The decision was hailed as a major victory for climate justice, particularly for developing nations and small island states who had fought tirelessly to bring the issue to the table.

But what changed? Why did developed countries, many of whom had previously blocked the idea, finally come on board?

Several key shifts helped pave the way:

The result was a long-overdue acknowledgment that the climate crisis is not just about future risks – it’s about real losses happening right now, and the urgent need to respond.

The agreement struck at COP27 was a major political breakthrough – but it was only the beginning. In the two years since, the focus has shifted to the harder part: turning promises into action.

Here’s how things have unfolded since 2022:

At COP28 in Dubai (2023), countries formally agreed on how the Loss and Damage Fund would be structured and governed, solidifying its role as the first truly global fund for responding to climate-induced loss and damage.

Key decisions included:

By late 2024, at COP29 in Azerbaijan, the fund was declared officially operational.

This marked a major step forward, but some cracks were already starting to show.

In a move that sparked international criticism, the United States withdrew from the fund in early 2025 under the Trump administration, walking back its initial pledge of $17.5 million. Climate advocates warned this could undermine confidence in long-term financing, especially if other countries followed suit.

In April 2025, the fund’s board approved a $250 million start-up package for use through 2026. Funds are being distributed as grants, primarily focused on:

Grants range from $5–20 million per project, prioritising national-scale interventions in the most climate-vulnerable countries.

But some governments, particularly in small island states and parts of Africa, have raised concerns about slow disbursement timelines, access barriers, and a lack of transparency around how decisions are made. Organisations like the Loss and Damage Collaboration have continued to call for greater inclusivity, accountability, and urgency in how the fund is governed and delivered.

But how does the fund actually function in practice?

While the creation and operational launch of the Loss and Damage Fund represent major milestones, serious questions remain about whether the fund can deliver at the scale and speed required. As of mid-2025, several key challenges are threatening to slow its impact.

If the fund is to succeed, it must be not only well-funded, but also accessible and responsive in responding to loss, especially for the countries on the front lines of the climate crisis.

While the Loss and Damage Fund is still in its early stages, significant steps are being taken to prepare for the start of funding disbursements. In early 2025, the Fund’s board approved a US $250 million start-up package for the 2025–2026 period, marking the initial phase of its rollout.

The Fund aims to prioritise rapid-response support for climate-vulnerable countries, particularly those affected by sudden disasters such as storms and flooding, as well as those grappling with the long-term impacts of rising sea levels and extreme heat. Formal disbursements are anticipated to begin in early 2026, pending finalisation of the application and approval processes.

At least 50% of the initial funding has been reserved for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) – regions most exposed to climate impacts but with the fewest financial resources.

This includes support for:

The early disbursements are being guided by a temporary operating framework known as the Barbados Implementation Modalities. Key features include:

This framework is designed to get funds flowing quickly while longer-term systems and new funding arrangements are finalised.

Rather than funneling aid through international NGOs or third parties, the fund is working directly with national governments and public agencies, giving countries the ability to lead their own recovery strategies.

To support this, the Board also plans to coordinate with existing mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund, aiming to streamline disbursement by working through already accredited partners.

This signals a move toward damage funding arrangements rooted in sovereignty and self-determination, rather than dependency.

The creation of the Loss and Damage Fund marked a long-overdue shift in the global climate conversation, one that recognises not just emissions, but responsibility, and the reality of a growing climate emergency. For countries on the front lines of climate disaster, it's more than just a pot of money - it's a signal that climate justice is finally being taken seriously.

But symbolic breakthroughs only matter if they’re followed by real results.

The biggest challenge remains what it has always been - finance. Current pledges, while meaningful, are still dwarfed by the actual costs of climate-driven loss. Without sustained and predictable funding, the promise of the fund risks being reduced to one-off gestures rather than long-term impact.

Public and political pressure is mounting, reinforced by stark warnings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) about the increasing severity and frequency of climate impacts. In the face of worsening climate impacts, wealthy nations can no longer distance themselves from their historical role or their obligations to those now suffering the consequences.

And we must not lose sight of the bigger picture. While the fund plays a vital role in helping countries recover from climate-related losses, it is not a substitute for deeper climate action or a coordinated global political strategy to address the root causes of global heating.

At Greenly, we believe that achieving climate justice starts with action, and that businesses have a powerful role to play. While international funds like the Loss and Damage Fund support countries already facing climate devastation, the private sector must do its part to reduce emissions and accelerate the global transition to a low-carbon economy.

Our suite of sustainability services is designed to help companies do exactly that.

| Our services | Description |

|---|---|

|

Carbon footprint assessments

|

We calculate your Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, giving you a clear view of your environmental impact. |

|

Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs)

|

Get detailed insights into the emissions linked to your products, services, or supply chains, from raw materials through to disposal. |

|

Emission reduction strategies

|

We help you turn data into action, with tailored decarbonisation plans that align with your business goals and regulatory obligations. |

|

Compliance and reporting support

|

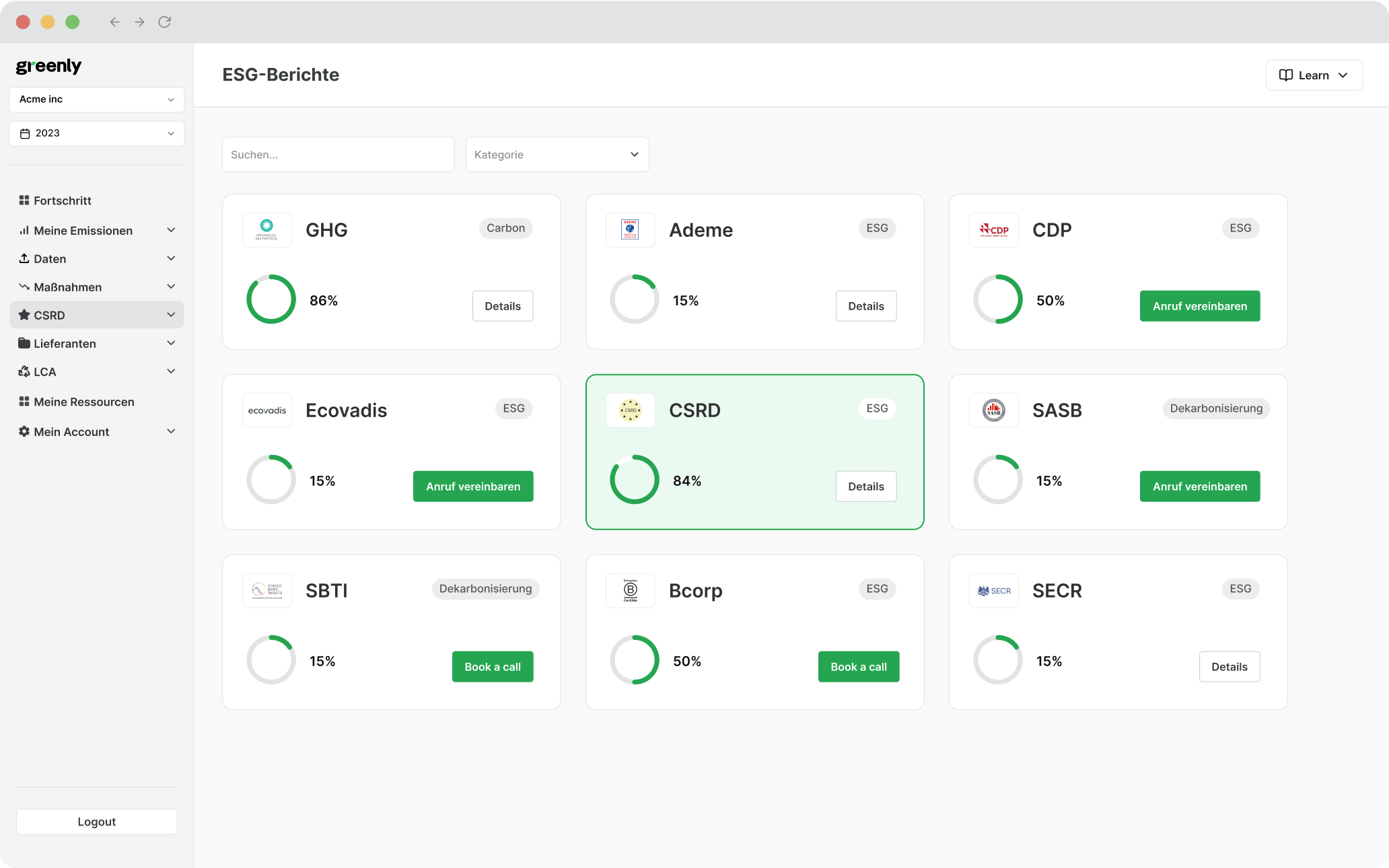

Whether it’s CSRD, SECR, or the latest EU regulations, we’ll guide you through your reporting requirements and help you stay ahead of evolving standards. |

|

Supplier engagement and Scope 3 optimisation

|

We provide tools and strategies to engage suppliers, fill in data gaps, and reduce value chain emissions across your entire business ecosystem. |

Get in touch with Greenly today to learn how we can help your organisation measure, reduce, and report its emissions – and become part of the global solution.